The tumultuous teens: a decade of upheaval

Times photo – Althea John

Lynda Lovejoy, left, and Vice President Ben Shelly shake hands on primary night as they think ahead to the Nov. 2, 2010, general election at the Window Rock Sports Center on Aug. 3, 2010.

DURANGO, Colo.

The teen years are noted for being stormy, and the 2010s on the Navajo Nation were no exception.

The top stories between 2010 and 2019 alternated between politics and the environment, with major developments on both fronts.

As 2010 entered with America’s first Black president in office, the Navajo Nation seemed poised to get its first female president in the person of New Mexico State Sen. Lynda Lovejoy.

Lovejoy did not prevail over former vice president Ben Shelly, but she became the first woman to survive the primary election, and by last year’s tribal presidential election, several women felt empowered enough to throw their hats in the ring, including one transgender candidate.

While several medicine people had gone on record opposing Lovejoy’s candidacy because of traditional prophesy, most of those voices were silent in 2018, possibly because none of the women made it past the primary.

The most notable election year of the decade, however, was 2014, when popular candidate Christopher Deschene was disqualified for not being fluent in Navajo, prompting much soul-searching on whether the language requirement was discouraging youthful candidates who may otherwise be qualified, and what, exactly, it meant to be “fluent.”

Navajo Nation Presidential candidate Chris Deschene greets the attending audience at the Window Rock Sports Center in Window Rock as the Navajo Nation primary elections begin to wind down. Deschene got the second most votes, 9,734, after Joe Shirley Jr. (Times photo – Donovan Quintero)

Finally the language requirement was clarified to let the voters decide whether a candidate spoke enough Navajo to qualify.

By that time it was too late for Deschene, and the election took place between former president Joe Shirley Jr. and the third-placer in the primary, Russell Begaye, who emerged the victor.

Joe Shirley did not manage to claim a third term although he ran in 2010 (hoping to overturn a rule limiting the president to two consecutive terms), 2014 and 2018, when he lost to then-vice president Jonathan Nez.

But he had already managed to leave an indelible mark on Navajo Nation history by reducing the Navajo Nation Council from 88 to 24 members effective 2011 and introducing gambling to the Navajo Nation.

By the end of the teens, the Navajo Nation had four casinos and the gaming enterprise had started expanding into the hospitality industry.

The other big story of the decade was the environment. As the drought steadily worsened in the early teens, President Ben Shelly found himself between a rock and a hard place. A proposed settlement of the water rights on the Little Colorado River, which would have included the Nation sacrificing a portion of its water rights in exchange for infrastructure, proved so wildly unpopular that he was forced to back down, leaving the Nation to take its chances in court.

A plan to round up Dinétah’s feral horses, which ranchers accused of drinking up and fouling the ever-scarcer watering holes, stirred an international uproar from humane organizations and even actor Robert Redford. It was eventually abandoned and the animals remain a problem, now numbering in the tens of thousands with few natural predators.

Water issues continued in 2015 as an estimated several hundred Navajos — including President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer — joined the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in protesting the construction of an oil pipeline beneath the tribe’s main water source, braving sub-zero temperatures, tear gas and rubber bullets.

A dam breach that released a million gallons of wastewater into the Animas River on Aug. 5, 2015, colors the river orange as it merges with the San Juan River, right, on Saturday in Farmington. Navajo Nation tribal officials have been visiting community members living along the San Juan River to inform them to not use or swim in the river’s water until further notice. (Times photo – Donovan Quintero)

In the summer of that year, the Diné had their own water issue to contend with, watching in amazement as the Animas River ran orange with dissolved metal compounds from an abandoned gold mine near Silverton, Colorado — the result of a botched containment effort by the US. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Navajo Nation joined the states of New Mexico and Utah in suing the agency and its contractor. As of this writing the litigation is still pending.

Then there was Bears Ears National Monument, created by President Barack Obama on Dec. 28, 2016, and reduced by 85 percent by President Donald Trump less than a year later. That’s also slogging through the courts.

But by far the biggest environmental story was the rapid dethronement of King Coal, which for decades had propped up state, local, and tribal economies in the Four Corners.

As prices for natural gas and renewable energy declined, power plant owners beat a hasty retreat from the dirty fossil fuel that had sustained generations of Navajo miners and a good chunk of the Navajo and Hopi tribes’ budgets.

In 2013, the Navajo Nation managed to stave off the closure of BHP Billiton’s Navajo Mine by creating a company to buy it, but there was no stopping the demise of the Navajo Generating Station and the two mines on Black Mesa that fed it.

Environmentalists had for years been pressuring the tribal government to create a plan to replace the revenue that would be lost when the plant closed, preferably by converting it to a sustainable energy producer, but as the last coal shovelful of coal was turned this past November, the only plan was to dig into the Permanent Trust Fund former President Peterson Zah had created in 1985 for just this eventuality.

Meanwhile the Navajo Transitional Energy Company, the tribal enterprise created to buy the Navajo Mine and then lead the Nation into a more sustainable energy future, purchased three more coal mines in Wyoming and Montana — a move that shocked not only environmentalists but the president and Council.

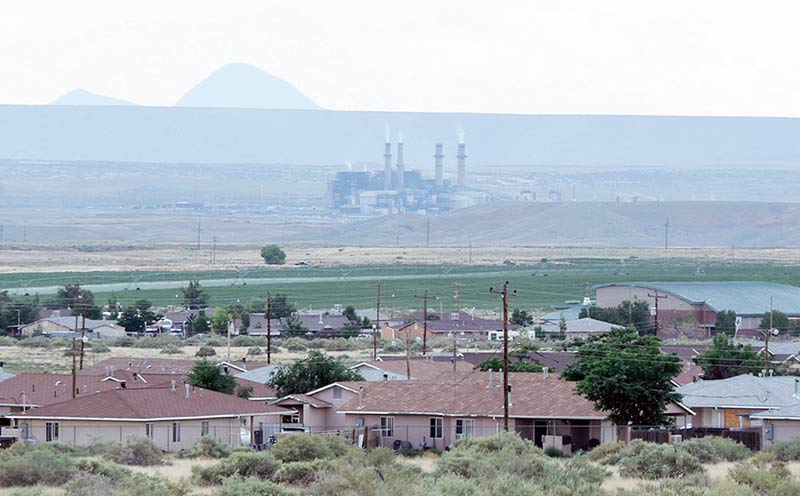

Navajo Times | File

The coal-fired San Juan Generating Station in Waterflow, New Mexico, pictured here, will close in 2022 if the New Mexico Public Regulatory Commission grants its permission. The PRC is currently hearing testimony on PNM’s plan to close the plant and replace it with a gas-fired plant and/or renewable energy.

The San Juan Generating Station in Waterflow, New Mexico, is next on the chopping block, slated to close in 2022 unless the state’s Public Regulation Commission approves a plan to convert it to a carbon capture facility.

We’re reporters of the news, not prognosticators. But it’s not too risky to predict that all these environmental issues will extend into 2020 and most likely beyond, joined by ones no one has even thought of yet as irreversible climate change takes hold.

We’ll be there to bring you all the latest, and we hope we can continue to rely on you to support your tribal newspaper, where you’ll find stories and views you won’t see anywhere else.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow