50 Years Ago: Long Walk twins, protest groups make the news

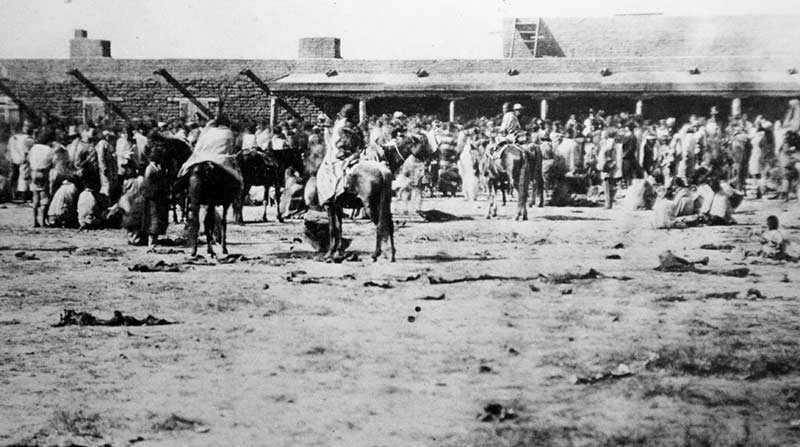

Navajos at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, 1864.

Mrs. Old Man Mud’s Wife and Mrs. Crooked Neck were back in the news this past week, according to the Navajo Times, which pointed out to its readers that these were the twin sisters who were honored this past summer for being the only ones alive who were at Fort Summer during the years of Navajo captivity.

The two, who were 103 years old, were honored during the Centennial celebration and then went back to their homes in Kayenta where they continued herding sheep and taking care of their homes.

Somehow, officials at the U.S. Social Security office heard of them and decided to honor them with an article in the department’s magazine, Oasis. The article included a photo that appeared in the Navajo Times of the twin sisters talking with Navajo Tribal Chairman Raymond Nakai.

The article gave a brief history of how the two were born at Fort Sumner and why the Navajos were there.

It is believed, said the article in the Times, that the two came back to the reservation in 1868 in a wagon since at the age of three, it is doubtful that they were able to walk that long journey.

When they were interviewed for the Oasis, they told the author that they had no memory of being at Fort Sumner. Both said they could remember being taken back to the reservation by their parents along with some of their other relatives.

In other news, the Times’ editor, Dick Hardwick, strongly urged readers of the tribal weekly to go out and buy a copy of a new book that was just published titled “The New Indians,” which gave a history of the Red Power movement that was now making headlines across the country with demonstrations and takeovers to bring attention to the plight of the Native American people.

The author of the book, Stan Steiner, pointed out in his book that the movement began in Gallup when a group of young Natives met during the 1960 Inter-tribal Indian Ceremonial and decided to form the National Youth Council.

The leader of the group was Clyde Warrior, a member of the Sioux Nation, who convinced a number of young Navajos, including Herb Blatchford Jr., that young Natives from all across the country needed to band together to fight injustice and blatant discrimination against Native people.

Warrior died in July 1968 from a liver ailment, but during his last eight years, said Hardwick, he worked almost full-time to get the youth council up and running and to recruit as many young Navajos as he could to the cause.

According to Steiner, the youth council would work with peaceful demonstrations and meetings with government officials to get changes made. But Warrior would later take his message further and promote the use of guns and violence to make non-Indians understand the message the young Natives were trying to get across, which then led to the creation of the American Indian Movement and other Indian groups that would later take over government buildings, hospitals and even an abandoned jail facility on Alcatraz island in the bay by San Francisco.

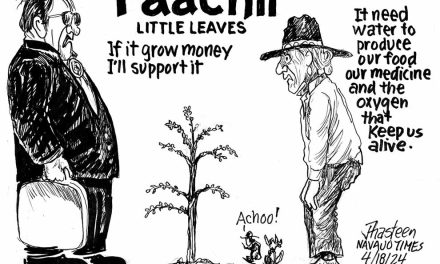

The youth council was the forerunner of a group of young Navajos who formed Indians Against Exploitation. IAE advocated for improvements in living conditions for Native dance groups who traveled every year to Gallup for the Ceremonial and who were housed in substandard buildings on the Ceremonial grounds.

The group also protested the way many Gallup businesses treated Native customers such as by being disrespectful and refusing Natives who came to Gallup to spend the whole day shopping the right to use their restrooms unless they purchased something.

The group lasted for several years and convinced the Ceremonial not only to improve conditions for Native dancers but to place Navajos in key positions so that the Navajos would have, for the firs time, a voice in how their culture was being portrayed.

The group had less influence, however, on changing the thinking of most business people in Gallup who looked down on members of the group and thought that not only their business but their lives were in danger.

At one meeting called by the city to address concerns of local business men who feared that then peaceful demonstrations by the group would eventually lead to riots where their businesses would be looted and destroyed, one business owner asked if he was legally in his rights to shoot IAE members if they walked into his business.

It never came to that, but accusations of racial discrimination are still being considered today by the Navajo Nation Civil Rights Commission not only in Gallup but also in Farmington and other border communities.

In that same issue, Hardwick wrote a column about Warrior’s death at the age of 28 and the fact that his parents were so poor that they could not afford to pay for a headstone to place on his grave.

Warrior had been planning to lead the delegation that was part of the Poor People’s March on Washington, D.C., in June but he was too ill and died just three weeks later.

The Rosebud Sioux Herald began a fund drive to raise money to buy a headstrong and Hardwick urged Navajo Times readers to donate as well.

And finally, this issue of the Times brought attention to the problems of Nathanial Mack III.

Mack claimed to be part Cherokee and said he was stationed in Germany as a member if the U.S. Army and was expecting to be discharged soon.

It seems that his life-long ambition was to be a Navajo so he has been writing letters to the Navajo Tribal Council asking that it approve a resolution adopting him into the tribe. He said that he has not received any reply from the Council to his many letters.

So he wrote a letter to the Navajo Times asking the newspaper to help him out.

“For many years, my heart has been there and I have wanted to be part of the tribe,” he writes. “My love lies with them. The honor and proudness is also a feeling I feel for the tribe. A sense of help is also constantly going on inside of me.”

In his response, which apparently was also sent in a letter back to him, Hardwick explained that there was no way he could be adopted within the tribe even if he was a member of the Cherokee Nation.

In order to be a Navajo, one had to have a blood quantum of at least one-fourth Navajo blood. This was not only a policy of the Navajo Tribe but it was also federal law and, although the tribe gets these kinds of requests a lot, they make no exceptions.

Whatever happened is not known.

Even though he could never be a Navajo, did he come to the reservation after his discharge? Did he perhaps marry a Navajo and raise some Navajo children? Or did he go back to Oklahoma and always thought that his life would have been so much better if he could have been adopted by the Navajos?

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow