Book on traditional teachings plows new ground

CHINLE

It’s hard to imagine a more scrutinized, more written-about people than the Diné.

SUBMITTED

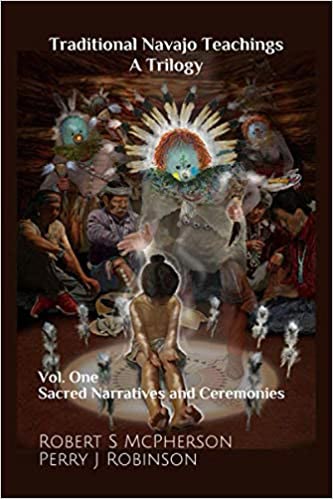

“Sacred Narratives and Ceremonies,” by Robert McPherson and hataali Perry J. Robinson, is the first in a trilogy on traditional Navajo teachings.

If you search “Navajo tradition” on amazon.com, no fewer than 202 titles come up. Since the 19th Century, anthropologists and traders have sat in on ceremonies and recorded their observations, often exploiting them for their own ends.

For almost as long, such documents have been controversial, with some practitioners arguing that ceremonies should not be shared with outsiders, and others countering that if the traditional ways are not recorded, they risk being lost. In the latter camp is hataalii Perry J. Robinson of Piñon, Arizona, who, through a series of interviews with historian Robert J. McPherson of Blanding, Utah, reveals what may be the most thorough and integrated study yet on the Navajo worldview from a Navajo perspective in “Traditional Navajo Teachings: A Trilogy” (2020, self-published but distributed by University Press of Colorado).

McPherson, while acknowledging the many contributions of previous authors, explains the difference between these books and others in his introduction:

“I have often heard Navajo people who have read a book on their beliefs point out that the detailed account under discussion might be accurate, but somehow the author still ‘missed it.’ Somehow the feeling, the understanding, the reasoning was absent.

“In other words,” he said, “a real insider perspective had been drained out of what had been recorded … Perry, who speaks English fluently, was able to maintain that connection.”

For his part, Perry explains why he was willing to reveal this information: “In the old days, when we asked questions of our elders, they would answer, ‘Don’t say that. Hold off. You’re not worthy to talk about that,’ so we never heard or understood the answer to our question; then the elder would die … As for those who think differently — you’re not supposed to talk about it, write it down, share it, or use it with outsiders — they are the reason that so many of our teachings are lost.”

He doesn’t divulge every detail of a ceremony, or sacred language that is only to be uttered during prayer; the idea is more to give the basis of the practice and how it relates to other practices and the natural world, the foundation of all Navajo belief.

In addition, there are chapters on the hogan, the sweat lodge, jish … any tools associated with ceremonial life that have their own stories and are to be cared for and treated as living beings.

As McPherson explains in the introduction, the interviews were originally commissioned by the Utah Navajo Health System to help staff and patients discern the relationship between Western medicine and traditional healing, but after six months of weekly interviews, Perry and McPherson ended up with enough material for a book — indeed, a trilogy.

They divided the material into three volumes: “Sacred Narratives and Ceremonies,” “The Natural World” and “The Earth Surface People” (full disclosure: this reviewer has only read the first book).

The teachings follow a pattern, with McPherson sort of setting the stage with what he knows about the topic through books, experience and his own extensive interviews with medicine people and other Navajos, then turning it over to Perry to explain the teaching in his own words. Perry acknowledges many times throughout the book that his perspective is not the only one; the stories and ceremonies vary slightly by region and even from family to family, but the key elements are the same.

It becomes quite obvious as he gently admonishes readers about, for example, improper attire or positions within the hogan, that he is addressing much of his narrative to Navajos who may read the books, while McPherson is aiming at the non-Navajo reader who sincerely wants to learn about the culture.

As a non-Navajo who has lived in the middle of the reservation for 16 years and been invited to my share of ceremonies, I found “Sacred Narratives and Ceremonies” invaluable as a key to understanding my Navajo friends. Even non-traditional people, like my husband’s students at Chinle High School, embody more Diné cosmology than they’re probably even aware of, as they are the product of untold generations taught to act and think a certain way. It helped me connect the dots, providing answers to questions I was hesitant to ask.

These books will undoubtedly be controversial, as both authors acknowledge. They should be read with reverence and respect, as they are about the closest thing there is to Navajo scripture. Whether or not one believes in the Navajo way, there are beautiful life lessons in these pages that anyone could benefit from.

McPherson is an academic first and foremost, and like all his books these are heavily footnoted, but his engaging narrative is accessible, and Robinson also speaks in a way that is clear and easily understood. He maintains, and demonstrates, that Navajo cosmology is both profound and simple. Although it may take decades to become a good medicine man, anyone can choose to live with the underlying principles of balance and harmony that ground the complex ceremonies.

My personal thought is that the books should be required reading for anyone who comes to teach, practice medicine or work on the Navajo Nation in any capacity — as well as young Navajos who seek a deeper understanding of their culture. If they expand your worldview even a little, they will be well worth the reasonable price.

The trilogy, in soft cover, beautifully illustrated, is available for $24.99 per volume from upcolorado.com or Amazon.com.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow