‘Unspoken traumas’: Interior report documents abuse, death at US-run boarding schools

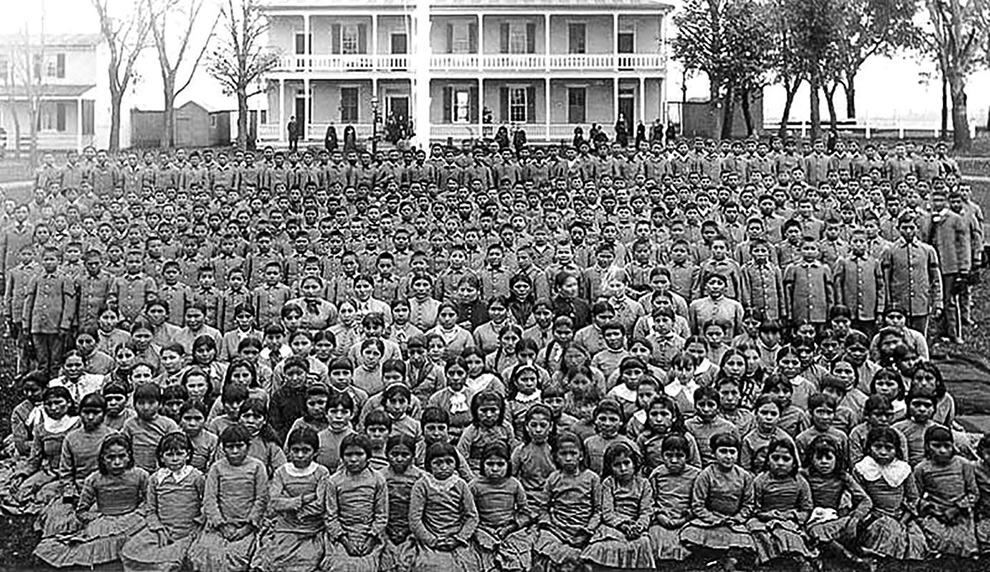

Courtesy photo | John N. Choate, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections

Carlisle Indian School student body around 1885, with the superintendent’s house in background. According to Wikipedia Commons, where this photo is found, from 1879 until 1918, over 10,000 Native American children from 140 tribes attended the boarding school in Carlisle, Pa.

SANTA FE

An explosive report released by the U.S. Department of the Interior last week represents the first step in accounting for the federal government’s role in a willful and deliberate use of federal boarding schools to forcibly separate Native children from their families, lands and culture in order to make way for the expansion of the United States over two centuries.

In an emotional press conference on March 11, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland announced that first volume of the “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report” lays the groundwork to confront intergenerational trauma caused by Indian boarding school policies.

“As the federal government moved the country west, they also moved to exterminate, eradicate and assimilate Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians,” Haaland said in a press conference. “The languages, cultures, religions, traditional practices and even the history of Native communities were targeted for destruction.”

The report confirms that the federal government’s “twin policy” of cultural assimilation and dispossession of Indian lands that targeted Native children through removal and relocation from their homes led to loss of life, physical and mental health, territories and wealth, use of tribal languages, and caused the erosion of tribal religious and cultural practices over generations.

“This has left lasting scars for all Indigenous people,” said Newland.

“There’s not a single Native American, Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian whose life hasn’t been impacted by these schools,” he said. “We haven’t begun to explain the scope of this policy era until now.”

DOI expects ‘thousands’ died

The investigation found that from 1819 to 1969, the federal Indian boarding school system consisted of 408 schools across 37 states or then-territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and seven in Hawaii.

The greatest concentration of schools was found in Oklahoma, with 76 boarding schools, in Arizona, with 47 schools, and New Mexico, with 43 schools.

“Tens of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their communities and forced into boarding schools run by the U.S. government, specifically the Department of the Interior and religious institutions,” said Haaland.

“It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies,” she said, “but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies…”

The investigation also identified marked or unmarked burial sites at approximately 53 boarding schools, but the DOI expects that number will increase as the investigation continues.

According to initial analysis, approximately 19 federal boarding schools accounted for over 500 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian child deaths, but that number is also expected to increase as well.

“Based on initial research, the department finds that hundreds of Indian children died throughout the federal Indian boarding school system,” Newland states in the report. “The department expects that continued investigation will reveal the approximate number of Indian children who died at federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.”

‘Identity alteration’

The DOI investigation affirms that education was used as a weaponized means to an end by the U.S. government, justifying policies that subjected Indian children to systematic militarized and “identity-alteration methodologies” in the boarding schools.

These included renaming children with English names, cutting their hair, wearing of uniforms, and forbidding the use of their languages, religions and cultural practices in order to compel them to adopt Western practices and Christianity.

Lack of compliance with rules by students was subject to forms of punishment, including solitary confinement, withholding of food, flogging, whipping, slapping and cuffing.

The report also states that “rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse,” disease, malnourishment, overcrowding, and lack of health care in the boarding schools are well-documented and child manual labor was incorporated into curriculums in addition to vocational training.

“I come from ancestors who endured the horrors of the Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead,” said Haaland.

“Now, we are uniquely positioned to assist in the effort to recover the dark history of these institutions that have haunted our families for too long,” she said.

The DOI said it will not make public the specific locations of burial sites to protect against grave-robbing, vandalism, and other disturbances, but will consult with tribes individually about recovering children.

“Many children never made it back to their homes,” said Haaland. “Each of those children is a missing family member, a person who was not able to live out their purpose on this earth because they lost their lives as part of this terrible system.”

Breaking family ties

Referencing historical government records, the report cites that, even beginning with President George Washington, the stated policy of the federal government (in pursuit of acquiring Indian lands) was to replace “the Indian’s culture” with its own.

As documented in U.S. Senate communications justifying assimilation and land dispossession, this was considered “advisable” as the “cheapest and safest way of subduing the Indians, of providing a safe habitat for the country’s white inhabitants, of helping the whites acquire desirable land, and of changing the Indian’s economy so that he would be content with less land.”

The theory was that the “problem of the (Indian)” could be solved by educating the children, not to return to the reservation but to be absorbed into the white population, which involved the permanent “breaking of family ties.”

Furthermore, there is evidence the United States “coerced, induced, or compelled” Indian children to enter the Federal boarding school system without their parents’ consent.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies, including the intergenerational trauma, caused by forced family separation and cultural eradication which were inflicted upon generations of children as young as four years old are heartbreaking and undeniable,” said Haaland.

In a personal anecdote, Haaland, who is from the Pueblo of Laguna, said that when her maternal grandparents were only eight years old, they were “stolen” from their parent’s culture and communities and forced to live in boarding schools until the age of 13.

“The fact that I am standing here today as the first Indigenous cabinet secretary is testament to the strength and determination of Native people,” said Haaland.

“I am here because my ancestors persevered,” she said. “I stand on the shoulders of my grandmother and my mother and the work we will do with the federal Indian boarding school initiative will have a transformational impact on the generations who follow.”

Boarding school funding

To add insult to injury, funding for the federal Indian boarding school system may have included both congressional appropriations and Indian treaty funds held in tribal trust accounts for the benefit of Indians by the United States.

While the exact amounts are not yet confirmed, this would indicate that proceeds from the destruction of the tribal land base were used to pay the costs of taking children from their homes and placing them in boarding schools.

A large portion of funds were also apportioned to Christian missionary organizations that were prominent in the effort to “civilize the Indians.”

The initial investigation shows that approximately 50% of federal boarding schools may have received support or involvement from a religious institution or organization, including funding, infrastructure and personnel.

Those same religious institutions and organizations were often paid by the federal government on a per capita basis for children to enter federal boarding schools that they operated, which could have incentivized overcrowding.

The report also notes that Indian territorial dispossession and assimilation through education extended far beyond the boarding school system, with an identified 1,000 plus other federal and non-federal institutions, such Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages and dormitories.

Next steps

Newland said the report presents an opportunity to now “reorient” federal policies to support the revitalization of tribal languages and cultural practices and counteract nearly two centuries of policies aimed at their destruction.

He said in order to begin the process of healing from the violence and the harm caused by the assimilation policy, the DOI should begin to revitalize culture including languages, cultural practices, traditional food systems, and intra-tribal relations.

Other recommendations for next steps, Newland said, include a full investigation to account for total number of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children who attended federal Indian boarding schools, including names, ages, and tribal affiliations.

The probe should confirm the total number of marked and unmarked burial sites and detail the health and mortality of Indian children.

Newland wants to quantify the amount of financial and other support the federal government provided to support the operations of the boarding school system and identify religious and state institutions and organizations that received federal funding for that purpose.

He also wants to confirm how much of that funding came from tribal or individual Native trust funds.

In a broader mission, Newland would like the DOI to identify all surviving boarding school students, document their experiences and recognize the generations of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children who lived through the federal boarding school system with a memorial.

“Together, we can help begin a healing process for Indian Country, the Native Hawaiian community and across the United?States, from the Alaskan tundra to the Florida everglades, and everywhere in between,” he said.

‘Road to Healing’

In response to Newland’s recommendations, Haaland announced the launch of “The Road to Healing” tour to allow survivors of federal boarding schools to share stories, connect communities with trauma-informed support, and facilitate collection of a permanent oral history.

Until now, the U.S. government has not provided a forum or opportunity for boarding school survivors or their descendants to voluntarily detail their experiences.

“The department’s work thus far shows that an all-of-government approach is necessary to strengthen and rebuild the bonds within Native communities that federal Indian boarding school policies set out to break,” added Haaland.

She said the federal policies that attempted to “wipe out Native identity, language and culture” continue to manifest in the pain tribal communities face today, including cycles of violence and abuse, disappearance of people, premature deaths, poverty, mental health disorders and substance abuse.

“Recognizing the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning,” she said. “To address the intergenerational impact of federal Indian boarding schools and promote spiritual and emotional healing in our communities, we must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past.”

The full 102-page Federal Indian Boarding School Investigative Report is available at: www.bia.gov

As a public service, the Navajo Times is making all coverage of the coronavirus pandemic fully available on its website. Please support the Times by subscribing.

How to protect yourself and others.

Why masks work. Which masks are best.

Resources for coronavirus assistance

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow