UW alumnus and Diné scientist co-finds Project Enable, a new Navajo-English dictionary for scientific terms

By Chael Moore

Special to the Times

ALBUQUERQUE

What are the words for bacteria and DNA in the Diné language?

They are ch’osh doo yit’íinii and iiná bitł’óól, respectively.

Project Enable, an online dictionary resource that launched in 2021, has done the work to provide not just one translation but 250 scientific terms and concepts from English into Navajo.

Project Enable is co-founded by Sterling Martin, Joanna Bundus, and Susana Wadgymar, a team of biologists who met at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Toronto in Canada. In 2019, they brainstormed how to merge their science worlds with the Navajo community.

Project Enable stands for “Enriching Navajo as a Biology Language for Education” and encourages the use of Diné Bizaad by providing the Navajo community with new and updated scientific terms while also providing the opportunity to fuse traditional knowledge with current scientific concepts.

The project supports language preservation and revitalization efforts and invites those interested in science to participate in the global scientific community or with their families.

Getting together

Submitted

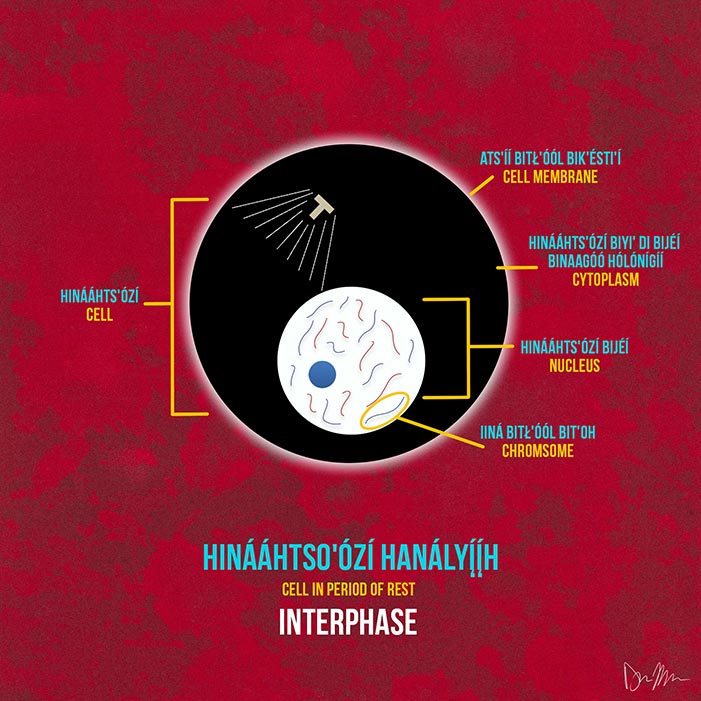

Dakota Mace, a Diné artist, illustrates Interphase from the cell cycle for Project Enable.

From weekly discussions over Zoom beginning in 2019, working through a pandemic, and gathering funding, they worked closely with high school biology teachers from the Navajo Nation, a Diné language expert, and other community members. Collectively, they all helped to identify which scientific words they wanted to translate, how they would solve them, and eventually create the site that exists today.

Sterling Martin is a Diné scientist who grew up in Shiprock. He is Kinłichíi’nii and born for Tódích’íi’nii. Martin received his undergraduate degree in biochemistry from the University of Iowa, and his master’s in biophysics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is one of the co-founders of Project Enable.

The project was partly inspired by the language barrier Martin was experiencing with his family during his undergrad and graduate years. The disconnect was apparent when his family members struggled to understand what their son/grandson was studying at university.

“I was an undergrad at the University of Iowa. I was doing research there and taking science classes, and one of the big things I noticed was there was no way of talking about what I was learning in the lab and classes with my family in Navajo,” Martin said. “The only way to communicate that was in English, but there was a disconnect between this scientific language into the Navajo language, and it wasn’t going well.”

He quickly discovered this disconnect was an issue across the Navajo Nation, not just with scientific terms but in other areas such as health care and environmental issues.

Susana Wadgymar, from South Texas, is currently an assistant professor in the biology department at Davidson College in North Carolina. She received her graduate degree at the University of Toronto, where she met Bundus. With a background in education, Wadgymar helped with Project Enable’s approach to reach students and research what would benefit middle and high school students the most as a first step in their project.

“We started with, ‘What are the foundational concepts that students might need to know in middle or high school to prepare them to pursue more advanced science classes?’” Wadgymar said. “We started with a pretty broad list, but we had high school teachers from the area actually go through and indicate which words they thought were foundational and would benefit students to be able to learn in both languages.”

Following the creation of their list, teachers and founders of Project Enable went through every word, one by one. They wrote their English definitions and examples of how they could be used in a sentence, ensuring they were appropriate for middle and high school learning.

Joanna Bundus, a current director of research for a startup company in Madison, Wisconsin, received her Ph.D. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology from the University of Toronto, where she met Wadgymar and was a postdoc fellow at UW-Madison, where she had met Martin.

Bundus and Martin met during one of the labs they shared at UW-Madison and would have conversations about the Diné language and discussions about the literal translations of some Diné words in their free time.

As a co-founder of Project Enable, Bundus found it fascinating and brainstormed with Martin on how they could get these terms online. Bundus was vital to getting Project Enable on its feet by connecting with colleagues such as Wadgymar, who could support their ideas and later expand their team to educators, linguists, and family members.

Creating Project Enable

The first step in developing Project Enable was identifying the words most helpful to translate. The second was to find someone who could translate them.

A Diné linguist, Frank Morgan, who is ‘Áshįįhí and born for Hashk’ąą Hadzohí, was recruited to help with the bulk of translations. With a background in biology and previous experience translating for other projects, Morgan met the criteria and was trusted to translate for Project Enable.

“Navajo isn’t really a written language, so we needed someone who could read and write the language as well. That was another ability that Frank demonstrated through all of his previous work. We could come up with a definition of the terms, then Frank uses his process to come up with the Navajo terms, but those also need to be validated,” Martin said.

It was important that each translation was under four words and scientifically accurate but also accurate in Navajo so it could make sense to the public. Words that were too complex to translate were omitted to avoid confusion.

“We had to try to be succinct with what we were saying. If you make a word too drawn out, you can easily lose the meaning of the word. For example, we had to be careful with words like ‘negative feedback loop,’ a biology term. Still, when we were testing that back home, they originally thought of negative feedback as like you did something wrong,” Martin said. He explained why some words were translated, and others weren’t or how words were broken down.

Members of Martin’s family were also recruited to test-run some of the translations to ensure that their ideal audience could understand what was being conveyed and that spellings and pronunciations were correct.

Once translations were complete, Martin’s grandmother, mother, and father went to the studio at UW-Madison and recorded these words for Project Enable to add to their website. This was to ensure that community members unable to read or write Navajo could utilize their website too.

Overcoming barriers

Martin and Bundus discovered that many words they were searching for did not exist in Navajo yet. At the beginning of this project, approximately 30 common terms, such as glucose or cell, existed, but it wasn’t enough, thus encouraging them to create new ones or update previous words.

Martin explained that this was potential because many physical Navajo-English dictionaries are not digitized on the internet or available to the public. Documents such as pamphlets or dictionaries have gotten lost in the print world.

“We are currently discussing who would fund that kind of research because it falls outside of the bounds of what funders think of archives. They want us to be looking at 500-year-old books and don’t necessarily think of pamphlets from the 90s as containing really critical information that is going to be lost if someone doesn’t digitize it quickly,” Wadgymar said.

Without a proper archive department established in the Navajo Nation, tracking down these physical documents to make them accessible on the internet required additional labor and a bigger team to execute, which Project Enable could not do at the time.

“This lack of digitization affected the project’s ability to obtain grant funding,” Bundus said. “It’s actually been a slightly frustrating thing because it’s so important to get it online, but lots of the grants that are available for this kind of work are only for ‘rare or totally dying languages,” Bundus added.

Despite the Diné language being on the verge of being endangered, there is still not enough urgency in obtaining many grants in this field of work. Gathering funding has been a priority for Project Enable to continue compensating the individuals who have contributed to their project and plans for their future.

A website for the people

Ensuring the Navajo community can easily access their site and engage with these terms was crucial. Limited access to reliable Wi-Fi and technology is an issue for many individuals who reside in the Navajo Nation, which Project Enable considered when creating their site.

To address this issue, Ira Fich, a colleague who specializes in web accessibility and open-source tool kits, created a user-friendly website that can be loaded from a public computer, laptop, or phone and requires little data usage. Creating an app was voted against due to constant updates that need reliable Wi-Fi, cell service, or a specific kind of smartphone that can download apps.

“We specifically decided not to go with an app because it’s hard to keep an app updated, and not everyone has access to a smartphone, but this website is small enough that it stays in the phone cache, so you don’t have to reload it every time,” Bundus said.

Project Enable launched officially in September 2021 and has approximately 250 translated terms on its site, with plans to expand its list in the coming years. The project is in its final stages, with plans to add audio and visual components to their site to be more accessible for those who cannot read or write Diné. Audio will help pronounce words, and graphic elements will depict what these words look like.

For each term, the site currently offers the scientific definition in English and Navajo, a “literal” translation broken down in both languages, and examples of how it is used in a sentence or exists in our everyday lives. A QR code has also been generated to easily access their dictionary to anyone who scans it with their smartphone.

Project Enable’s logo was created by Diné artist Duhon James and features a corn stalk, a microscope, water droplets, and the four sacred mountains, amongst other elements inspired by Navajo culture. They have also collaborated with other Native artists, such as Dakota Mace, to create diagrams and illustrations they can later pair with each word. They are currently working on uploading these new elements to their site.

Future of Project Enable

Project Enable plans to produce more educational material that can be distributed amongst schools and students and seeks to establish more community partnerships in the Navajo Nation. They wish to expand their project beyond biology into medical terminology and environmental issues.

They started small with 250 translations and a successful website launch, but they have bigger plans. Ideas to create educational pamphlets, classroom worksheets, coloring books, and posters have been discussed, but without adequate funding and trusted members in the community who can help distribute their work, their ideas to expand could be stalled. They hope to work with those who can help them get these materials into classrooms and people’s everyday lives.

In the meantime, the team of Project Enable will be preparing to present at the 2023 Evolution Conference in Albuquerque in June. Evolution is a science conference founded in 1989 that spans over 2-5 days and consists of virtual and in-person talks and an opportunity for individuals to network with other scientists and science enthusiasts.

Project Enable’s topics this year will focus on how to best educate and mentor Indigenous students in a way that is culturally relevant and respectful to them, said Wadgymer. Other topics include the current relationship between science and Indigenous people and the history associated with that, and how to best recruit and mentor Indigenous students through STEM and into higher education.

There is a registration fee to attend, and it opens in February 2023. However, students taking STEM-related courses at Diné College will have an opportunity to receive a stipend for listening and the opportunity to present their research at the conference.

The founders of Project Enable are eager to build community relationships, mentor students in STEM, and put some of their ideas in motion. Those interested in collaborating with project members are encouraged to visit their website and send an email. Diné artists interested in creating illustrations for the dictionary’s terms are also encouraged to reach out.

Project Enable believes that it’s important to make knowledge accessible and relevant for everybody, but it is also culturally aware and sensitive to the people it’s made for. They are motivated to break down language barriers and encourage diverse backgrounds and perspectives to exist in labs, research, and classrooms, to improve science and ensure that science is for everyone.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow