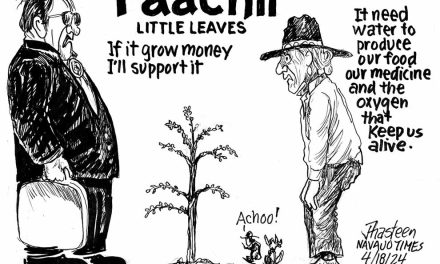

Reclaiming the range

Navajo Times | Cindy Yurth These two ewes and three lambs are all Francis Lester has left of his original herd of 78. Like other ranchers on the NPL, Lester has had to reduce his herd to 10 sheep units to qualify for a reissued grazing permit — but the two ewes he kept were pregnant and now he is officially out of compliance again, since he also has two horses.

Reissuance of NPL permits is ‘bittersweet’

WHITE CONE, Ariz.

Francis Lester remembers back in the 1960s when his grandmother ran 350 sheep and 34 horses on this remote patchwork of mesas and meadows. And she wasn’t alone.

Navajo Times | Cindy Yurth

These two ewes and three lambs are all Francis Lester has left of his original herd of 78. Like other ranchers on the NPL, Lester has had to reduce his herd to 10 sheep units to qualify for a reissued grazing permit — but the two ewes he kept were pregnant and now he is officially out of compliance again, since he also has two horses.

“When it was time for lamb auction at Francis Powell’s trading post, there was just a sea of sheep,” Lester, 53, recalled. “Someone would yell, ‘Hey, I’m going to butcher,’ and everybody would go to their tent to eat.”

These days, Lester’s “herd” comprises five sheep and two horses — and he’s still barely in compliance with the 10 sheep units that will be allowed when grazing permits are reissued on the Navajo Partitioned Land, since a horse counts as four sheep.

“I had 78 sheep,” he sighed. “I gave 76 away. But then both my ewes lambed, and one had twins. I said, ‘Come on, girls! We’re supposed to be reducing!'”

As White Cone’s grazing committee representative, Lester has to set an example before he can tell everyone else to reduce. On one level, “It’s heartbreaking,” Lester admitted. On another, “The livestock owners are really excited to finally be getting their permits back after 43 years.”

“It’s bittersweet,” echoed Leo Watchman, director of the Navajo Nation Department of Agriculture. “Ten sheep are not enough to make a living. But it’s a start.” In 1974, when the Joint Use Area shared by the Navajo and Hopi tribe was partitioned so the federal government could determine the leasing rights and allow coal mining on Black Mesa, all grazing rights were canceled until each of the tribes came up with a range management plan. The Hopis put one together in a year. The Navajos finally got one together last year.

Basically, said Lester and Watchman, a succession of tribal councils just lacked the political will, and the BIA never pressed them. “It was just easier,” observed Lester, “for everyone to look the other way.” Meanwhile, a lot of stuff happened. At first, there was anguish. Plenty of people were still alive who remembered the livestock reduction of the 1930s, and it felt like it was happening again.

To read the full article, pick up your copy of the Navajo Times at your nearest newsstand Thursday mornings!

Are you a digital subscriber? Read the most recent three weeks of stories by logging in to your online account.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow