Sense of homesickness pervades Intermountain exhibit

Navajo Times | Cindy Yurth

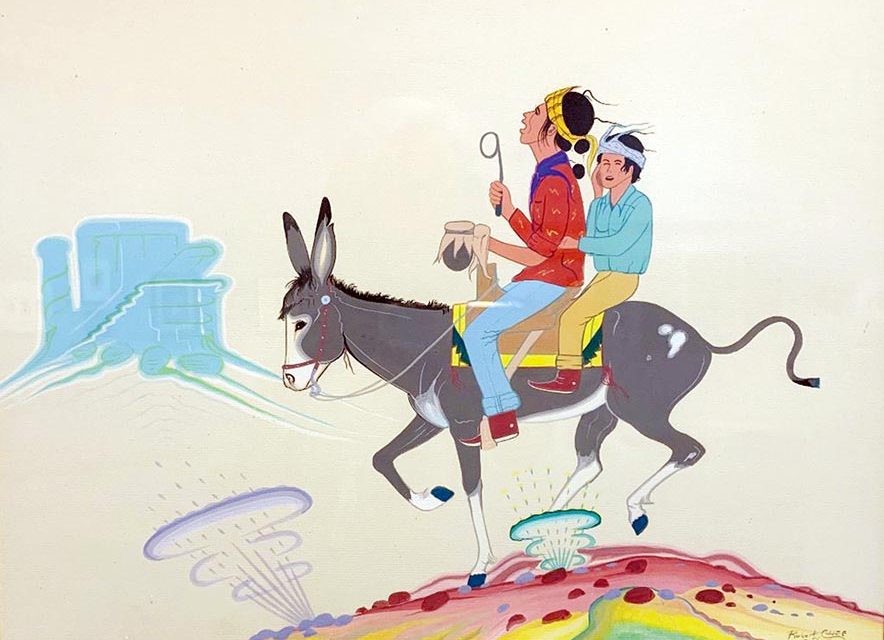

Robert Chee's painting "The Singers," on display as part of the "Returning Home" exhibit at the Navajo Nation Museum, incorporates the strong, linear style of his art teacher, Apache artist Allan Houser.

WINDOW ROCK

My husband is a high school teacher, so I’ve been to my share of high school art shows on the reservation.

Although there are definitely scenes of Diné bikeyah, faces of grandmas and grandpas, and some political themes, for the most part Navajo kids are painting and drawing the things that interest most teenagers these days: sci-fi and animé characters, superheroes, mythical animals and sports.

But what if they were in school hundreds of miles from home, in an all-white town, at a time most Navajos didn’t know much English?

The answer to that question can be found in a quiet, evocative exhibit currently at the Navajo Nation Museum: “Returning Home: The Art and Poetry of Intermountain Indian School, 1954-1984.”

In a thoroughly sampled collection that includes writings, drawings, painting, linocuts, murals and even a couple of videotapes of performing arts, a central theme emerges: home.

The subjects are red rock and yucca, hogans and hair buns, horses and sheep, faces of family members the students would only see during summer vacation.

Observed printmaking instructor Jim Westergard in an interview quoted on a plaque, “Their images were sourced from their memories, frequently depicting either Navajo customs, dress and environment. I would frequently have conversations with individual students regarding the images and I always detected strong home-sick moods.”

The arts, which were emphasized at the sprawling Brigham City, Utah, campus — a converted World War II military hospital — gave students a voice when they were caught between two languages and sometimes didn’t have a complete vocabulary in either.

Vivid colors and happy family life characterize the paintings, while the poems (a large number are preserved, thanks to Intermountain having its own printing press and literary magazine) often focus on darker themes like the racism they encountered off the reservation.

“Ripe were my dreams, contented, in tattered jeans,” wrote Henry Tinhorn, who went on to have an anthology published. “Until the silences of the violets open my eyes. Two words and a mouth were all it took: ‘Dirty Injun!’”

While a few Intermountain alumni went on to have careers in the arts, many talented artists ended up in the trades. Welding and construction were also emphasized at the school, since the common knowledge was that few Native Americans would go on to college.

Those who did make it in the art world sometimes didn’t last long. The Vietnam War claimed Tinhorn; the talented Robert Chee, who proudly identified himself as “artist” in the 1956 yearbook, survived a tour in the Army, but passed away three years after his discharge, in 1971.

The plaque with his picture doesn’t say to what he succumbed. PTSD? Alcohol? Then as now, the traps for young Native men were many.

It’s one thing to read about the isolation of the boarding schools, but to see it in students’ art and “hear” it in their poetry gives it a new dimension. This unassuming but thorough exhibit deserves a look, and be sure to give it some time.

“Returning Home,” assembled by Diné historian Farina King and Brigham Young University professors Mike Taylor and James Swensen, will close with a reception from 4:30 to 6:30 p. m. March 6, featuring guest lectures and refreshments. It is free and open to the public.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow