‘Something good, something positive’: Diné painter David K. John expresses beauty of culture

Courtesy photo | David K. John

Artist David K. John stands in front of a mural he painted called "White Buffalo Medicine," commissioned by the Kayenta (Utah) Arts Foundation last March.

WINDOW ROCK

In this season of uncertainty, when traditional Diné ceremonies have largely ceased due to COVID-19, appreciation for artist David John’s paintings that depict them has grown deeper.

John says the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has made many Diné pause and reflect upon their culture.

“They had to slow down in order to go back to their prayers, their songs and their teachings,” he said. “I know a lot of Navajos like the way I’m painting and it brings them back to their life growing up.”

People thank him for sharing his paintings of the Yé’ii and the blessings, he said, which he believes can help them cope with what’s going on in their lives and remember traditional ways.

“They get that positive light from my paintings when they see it,” said John. “That’s what I try to express – something good, something positive so people don’t get stressed out … there’s a way out and there’s good things ahead.”

In Navajo teachings everything has a negative and positive and you have to keep everything in balance, said John.

“That’s where the ceremony comes in,” he said. “That’s how you get to the good side, the Beauty Way. That’s how you balance life.”

That’s also how John views the impacts of the pandemic.

“Maybe the Holy People are telling us, look, you guys need to slow down,” he said. “You need to go back to your culture. Think about yourself and where you come from.”

Because of COVID-19, people have stayed close to home, he said.

“What COVID did is bring us back together with people spending time with their family at home when we had the lockdowns and all that,” he said. “They appreciate family again instead of being at work all of the time. They appreciate their relatives and grandmas and grandpas.”

John said for Navajos there is always a reason for things that happen, and that applies to COVID-19 too.

“It’s kind of put us back to where we came from and what we’re supposed to do,” he said. “In that sense, a lot of people are realizing they’re missing their way of life, their ceremonies, their songs. They’re hungry now. They want to have these ceremonies and learn more about it.”

Early years

When John was just a boy, he became one of the primary caretakers of his family’s traditional homestead in Jeddito/Keams Canyon, Arizona, where he was steeped in the teachings and stories of his elders.

“I stayed mainly with my great grandma and grandpa,” said John. “I helped around the house, took care of the livestock, herded sheep, and took care of the horses.”

His great-grandfather, John Slim Nez, a medicine man, also had a major influence on John and foresaw Navajos moving to the cities and losing their traditional ways.

“He knew what was ahead,” said John.

When his great-grandfather conducted ceremonies, young John often watched, helped out and absorbed the teachings.

That was just the way of life, said John.

Then he entered Toyei Boarding School and went on to study art and commercial illustration at Richfield High School in Utah when his talents first garnered attention.

He started selling his work, entering art shows and winning awards and scholarships.

“My art teacher encouraged me to continue with art,” he said.

After high school, John attended the Institute for American Indian Arts in Santa Fe where he was inspired by Native artists from other tribes.

“A lot of the people there were creating paintings of their traditional culture,” he said.

He went on to study at Brigham Young University and Southern Utah University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in arts.

When he was still in college, his artwork was chosen for the 1990 Census poster, which was distributed all over the United States and won a marketing award.

“That’s the first time I went to Washington, D.C., and they unveiled the poster next to the White House,” he said.

After that, John’s artistic career took off. He was accepted into Santa Fe Indian Market and was represented by the James Ratliff Gallery in Sedona, where he exhibited for more than 30 years.

Preserving way of life

After completing his education, John missed his family and longed to be back on the reservation, so he returned home to Keams Canyon.

It was at that time in his mid-twenties that he started doing representations of ceremonial life, with permission of his grandfather Smith Bahe, a Yé’ii Bi Cheii dancer, who said it was alright for him to depict Yé’ii as long as he didn’t copy the exact designs.

He also started making ceramic Yé’ii masks out of clay.

“After my grandpa passed, I started doing more of the Yé’ii remember him by, and remember all of the grandmas and grandpas – the traditional people,” he said.

John also realized many of the children were losing their cultural teachings and ceremonies.

“I wanted to do that kind of work to pass it on to the younger generation,” he said. “I thought, when I’m gone, when they see my paintings, they can ask other people what that represents…”

John paintings come from his own internal vision, interpretation and expression of Navajo mythology and history, he says, often leading to dreamlike, timeless abstractions embellished with ancient symbols.

At 57, his ubiquitous, award-winning artwork can be found in galleries and museums across the country and he is followed by many admirers, collectors and aspiring artists.

However, he still participates in the arts market circuit and enjoys sharing and talking about his work.

“A lot of artists like to see what I paint,” said John. “They come up to me and ask me all these questions. I found out that most of them want to do something similar but they don’t really understand.”

John said it can be hard for them because they didn’t grow up the way he did.

“They never learned about the ceremonies, or grew up herding sheep around grandma and grandpa,” he said. “I tell them you have to live it.

“I went to ceremonies, I listened to the songs, participated,” he said. “It’s hard to do spiritual paintings if you don’t really understand it, but if you live it, they can express that feeling.”

John said his generation is bridging the gap between the traditional elders and the youth, the old and the new, and Navajo and English.

“Many of the elders are leaving us, and they’re leaving with their traditional teachings, and a lot of these teachings aren’t being recorded,” he said. “They’re just being lost.”

He said a lot of songs are being lost too.

“If you listen to the songs – it’s a story, it’s a history…” he said.

‘The good way’

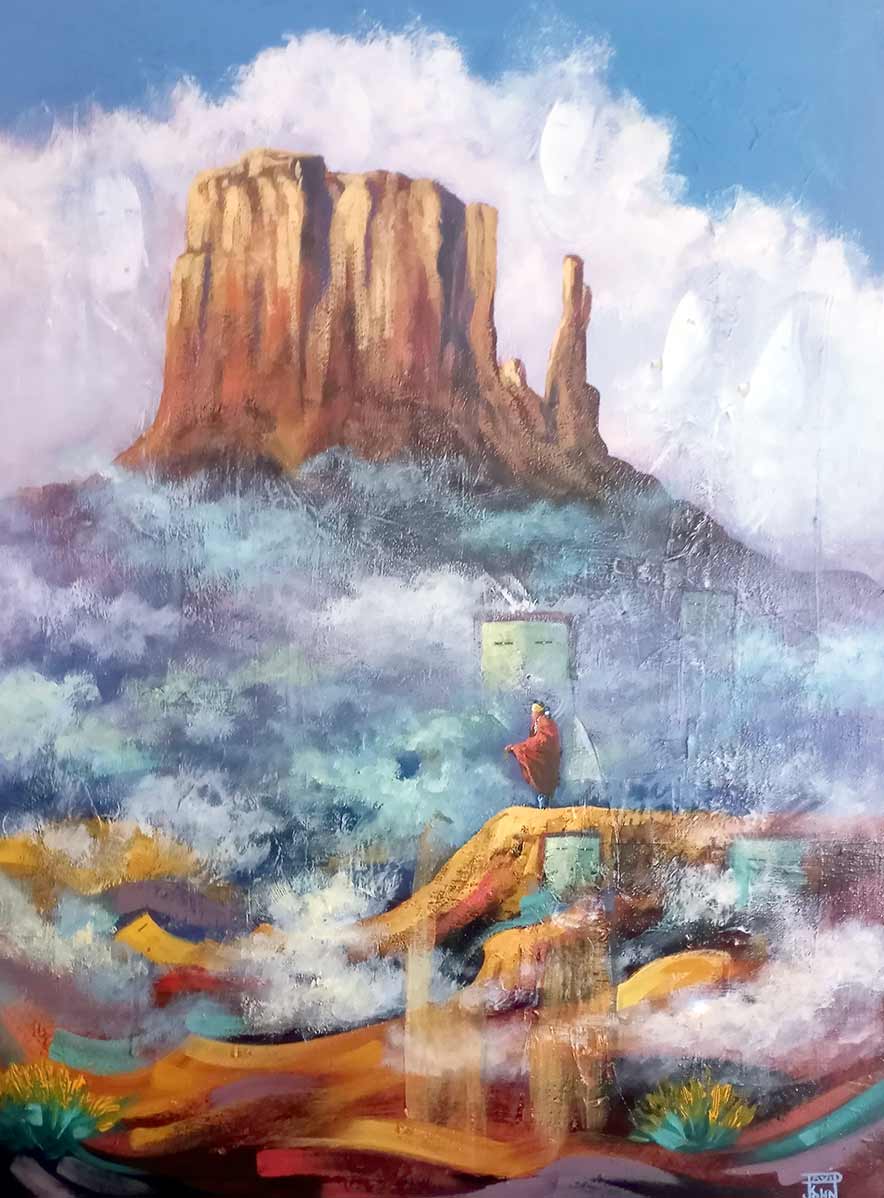

Courtesy photo | David K. John

“Monument Valley,” a 30×40 acrylic on canvas by David K. John.

John said even though some of his art themes are similar, his work is always changing and evolving.

For example, when his mother passed on about five years ago, John began adding hummingbirds to his paintings.

“They say the hummingbird is a holy bird that can fly to the heavens, a messenger between this world and the spirit world,” he said. “The hummingbird coming to you is a sign of good things and good luck.”

John’s use of vibrant colors, mixed with earth tones and Navajo designs, is singular and unique, bringing depth, texture and movement to his works.

“That is my style – I’m known for that,” he said. “It comes from the Navajo culture, the teachings. I use red to represent mother earth, blue is father sky, and yellow is for the sunshine.”

John says his use of bright colors comes from the teaching of the Hózhóǫ́jí, the Blessingway.

“I wanted to have my painting based on the good way, the blessing ceremony,” he said. “That’s what it represents. I try to use colors to bring positive things and healing.”

People can feel those things when they look at the paintings, he said.

He said the images he paints come to him in a variety of ways, whether from memory or experience.

Other times, he doesn’t have a specific idea, but just starts putting paint on the canvas and allows it to take on a life of its own.

“Once I put the paint on there, an image will appear, like a Yé’ii, or basket, or a bird or an animal,” he said. “From that it comes and I go with it and create the piece.”

He also incorporates dynamic Dinetah landscapes and skyscapes into his painting, drawn together to a focal point by the long horizon.

“I put Yé’ii in the clouds sometimes – rain spirits or rain deities pour water on the land,” he said. “For us Navajos, everything has spirits – animals, plants, air, trees…”

The coronavirus is also a spirit, he said, which is making people realize that in our fast-paced society, we have been neglecting Mother Earth.

“We have to go back and respect all of these things in order for it to go away,” he said.

In that way, the virus itself is a teaching, he said.

“It’s part of life,” he said. “We’re treating our Mother Earth not the way it’s supposed to be treated. It’s alive. It has spirit. The Earth and the Sky – we’re the kids in-between, and they take care of us.”

No doubt, John’s dynamic communication with the natural world, animated on canvas through his imagination and artistic mastery, brings to life the blessings of the spirit world.

Once the virus is gone, people will go back and do the Hózhóǫ́jí, the Beauty Way ceremony, and everything will be brought back into balance, said John.

“It will be good again,” he said.

David K. John currently resides in Kayenta with his wife Kathleen. His clans are Mexican (Nakaii Diné), born for Black Streak (Tsi’naajínii). His maternal grandparents are Edge Water (Tábąąhá), and paternal are Towering House (Kiyaa’ánii).

Information: davidkjohn1@gmail.com

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow