New book examines relationships that wove an economy

CHINLE

Considering how fascinating the history of the Navajo Nation is, it’s amazing how few aspects of it have made their way into books. Two subjects, though — the Navajo Code Talkers and the trading posts — have been pretty extensively covered.

Between memoirs and biographies of Indian traders, economics dissertations indicting the trading post economy and most recently the astoundingly thorough “Navajoland Trading Post Encyclopedia,” by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis (not to mention having lived through the tail-end of the trading post era myself), I thought I knew about all I wanted to about Navajo trading posts.

Between memoirs and biographies of Indian traders, economics dissertations indicting the trading post economy and most recently the astoundingly thorough “Navajoland Trading Post Encyclopedia,” by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis (not to mention having lived through the tail-end of the trading post era myself), I thought I knew about all I wanted to about Navajo trading posts.

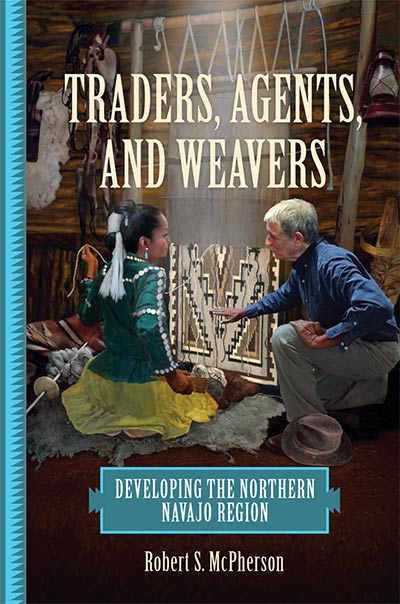

I put off reviewing “Traders, Agents and Weavers: Developing the Northern Navajo Region” (2020, University of Oklahoma Press) even though it is by one of my favorite local authors, Utah State University history professor emeritus Robert S. McPherson.

In fact, by its perspective, the book makes a unique contribution to the trading post literature, especially when read as a companion to McPherson’s other recent work on trading posts, “Both Sides of the Bullpen: Navajo Trade and Posts” (2017, University of Oklahoma Press).

In “Both Sides,” McPherson draws from first-hand accounts of traders and their customers over the years to show how the posts became sort of a buffer zone for two cultures that sometimes clashed but, at their best, mutually benefitted economically and in other ways.

But, one learns in “Traders, Agents and Weavers,” that is just part of the story. While the posts may have looked like bastions of free enterprise on the wild frontier, nothing could be further from the truth. The men and women who set up shop on the reservation were subject to pages of federal regulations — including, surprisingly, the prohibition of extending credit through pawn (though it seems to have seldom been enforced).

On the other hand, they were under the intense scrutiny of the local Diné headman, who could easily ruin them by organizing a boycott or, worse, complaining to the local Indian agent and having their license revoked if he felt the trader was not treating his people fairly.

The third point of the trade triangle was the weavers. Working with their local trader to figure out what their white patrons back East wanted to buy, these savvy women (and a few men) created ever-more-intricate patterns and styles of rugs — not something the Navajos used themselves until recently.

The traders helped them by procuring dyes and tools, paying top dollar for top quality, coaching them on sizes and colors that were selling well, and in the case of J.B. Moore in Crystal, actually sending the Navajo wool back east to be factory-cleaned and carded. It was these partnerships between trader and weaver that resulted in the regional styles we know today, named after towns with trading posts: Two Grey Hills, Crystal, Ganado Red, etc.

While they didn’t make the title, another factor in the development of the reservation were the missionaries, oftentimes single women sent out by their churches to establish schools in remote areas. Often the posts chose to locate near a mission school, which would have already had a rudimentary road, probably a water source and other infrastructure. The book profiles some of these folks as well.

Since the topic is so broad, McPherson zeroes in on an area roughly between Shiprock and Naschitti, New Mexico, on the eastern slope of the Chuskas, extending north to Teec Nos Pos and west to Burnside. The area had a plethora of posts which both competed and cooperated, and nurtured some larger-than-life characters to go with the scenery: Naataanii Nez himself (Indian agent William Shelton); leaders and medicine men like Bizhóshí, Little Singer, Black Sheep and Hastíín Klah; trading families like the Noels, the Davies, Newcombs, the Moores and the Wetherills.

What emerges is not only an economic history but a rare regional history, forged by clashes and cooperation between some particularly stubborn and intense personalities to whom the trader often played mediator.

By virtue of being based on primary sources, the book reads a bit unevenly; some of the traders (more often, their wives) were better writers than others; the stories of the Navajo leaders, most of whom never learned to write English, are told in quotations by Anglo contemporaries or oral history passed on to their descendants. The book also is not entirely objective; McPherson states in his introduction he’s attempting to counter the common thesis that all the traders were greedy capitalists exploiting the talents of the weavers for their own gain.

To assume the Navajos were naîve victims of unscrupulous traders is itself a paternalistic attitude, McPherson argues, citing ample evidence that the Diné were known as shrewd traders long before the white man came along.

Again, not all traders kept great records, and not all records have survived, but from what McPherson was able to surmise by a review of the ledgers, a lot of the traders were barely getting by — at least, they were faring much worse than their counterparts in the border towns, who weren’t subjected to such strict government scrutiny.

They lived on the reservation, he posits, because they loved the people and wanted to bring them the things they wanted and needed to thrive.

He has some harsh words for DNA-People’s Legal Services’ scathing 1972 report on the posts to the Federal Trade Commission, which proved the nail in the coffin of most of the last remaining posts, already decimated by the wage economy, the decline of weaving and livestock raising and other factors.

“Introducing tyrannical control and administrative demands onto an already challenged system of trade and a group of overworked owners proved to be too much,” McPherson writes in the book’s final chapter. “No doubt there were those who abused their positions, and every example given in the report had its point of genesis, but to broad-brush the entire system as intentionally corrupt pushed beyond the limits of fairness.”

Whether or not you agree, it’s a view that deserves to be heard, and McPherson backs it up with statistics and years of research.

Even if you’re already well read in economics or Navajo history, I guarantee you’ll find something of value in this tightly woven, richly textured story of the Four Corners.

“Traders, Agents and Weavers: Developing the Northern Navajo Region” is available in hardcover (with gorgeous cover art by Charles Yanito, by the way) for $39.95 at bookstores and as an Ebook starting at $16.17 on play.google.com and other platforms.

Highway 264,

Highway 264, I-40, WB @ Winslow

I-40, WB @ Winslow