The Mother Road's stepchild

Can Houck revive the mystique of Route 66 ... Navajo style?

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 33rd in the series.)

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

HOUCK, Ariz., May 2, 2013

(Times photo — Cindy Yurth)

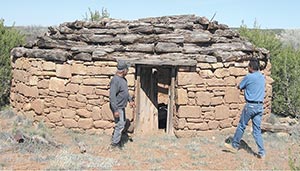

TOP: Austin Sam, Houck’s unofficial historian, shows Houck’s old meeting hogan to newly elected Chapter Vice President James Watchman Jr. Sam, 73, remembers sitting with his mother on the floor of the hogan for community meetings. The building, probably built in the early 1930s, became a family home when the present chapter house was built in 1956, but it was abandoned after a baby died in it.

SECOND FROM TOP: Anasazi artifacts like these leftover shards from arrowhead chipping are everywhere in Houck, making archeological clearances a nightmare. Growing up here inspired Austin Sam to study geology, hydrology and anthropology at the University of New Mexico, where he became friends with author Tony Hillerman and consulted with him on his books.

Houck at a Glance

Name - The chapter's namesake, James D. Houck, delivered the mail between Prescott, Ariz. and Fort Wingate, N.M. He set up a ranch at a spring known by the Navajo as Ma'iito'i, or Coyote Spring, at the confluence of Black Creek and the Rio Puerco. The place became a stagecoach stop and in 1884, when the post office was set up there, was given the name "Houck's Tank," later shortened to "Houck."

Population - 1,024 at the 2010 Census; chapter officials estimate it closer to 1,700

Land area - 147 square miles or 94,080 acres

Major clans - 'Ashiih’, Naasht'ézhi Tazhii'nii, Honágháanii, T—'áhán’, Kinyaa'áanii. There is also some German Jewish blood floating around the chapter, courtesy of a turn-of-the-century trader named Curt Cronemeyer. Cronemeyer was a notorious ladies' man, which, according to oral history, eventually led to his demise. In June of 1915, the story goes, a group of Navajo men confronted the 49-year-old trader at his store, accusing him of flirting with their wives. Cronemeyer protested his innocence, but the Navajos were having none of it and one of them shot him. However, an article in the Aug. 27, 1915 edition of the Coconino Sun has the Gallup sheriff tracking a group of Mexican bandits to El Paso, Texas, where they eventually confessed to the murder and were apprehended. Cronemeyer, described in the article as "eccentric," is the grandfather of Chapter Vice President James Watchman Jr.

Assets - A major transportation and tourism corridor, Interstate 40, bisects the chapter, as does the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad. In the past, both clay and industrial sand have been mined in Houck, but the only sand mine still operating is in Nahata Dziil Chapter. The chapter also contains a picturesque stretch of old Route 66, including several still-operating Indian stores.

Problems - The combination of an interstate highway and easily available alcohol has led to numerous fatal crashes in the area. Over the years, the chapter has managed to shut down seven or eight package liquor stores on parcels of private land within its boundaries and in nearby Lupton, Ariz., but two stores still operating in nearby Sanders and Chambers offer a steady supply of booze. Other problems are also caused by heavy checkerboarding in the area. For instance, the Navajo Housing Authority's plan for Houck spreads across parcels of trust, allotted and private land, requiring the chapter to obtain a slew of clearances before a shovelful of earth can be turned.

It was the 1950s. Eisenhower was in office, the post-war economy was ablaze, the men were back from the war and people were having families again.

Which, of course, meant family vacations.

John Wayne and The Lone Ranger were heroes, and every kid had either a cowboy or an Indian costume, or both. The American Southwest, long considered a worthless desert by most of the country, was suddenly a tourist paradise, especially with the advent of air conditioning.

Down the cross-country highway Route 66 floated caravans of glossy sedans, filled with pasty-skinned Easterners eager to partake of the Western mystique.

Savvy entrepreneurs were only too eager to oblige, setting up Indian-themed motels and curio shops full of tomahawks and feather headdresses.

Fortunately, there was enough overflow business for the real Indians. According to Houck Chapter Vice President James Watchman Jr., weavers and silversmiths set up shop between the kitschy bilagáana-run trading posts. The bilagáana traders were happy to hire locals so the tourists could meet "real Indians." For a shining moment, everyone was happy.

Then came the 1980s. The towns that had sucked off the teat of the Mother Road could only watch as Interstate 40 came blasting through, leaving an outdated parallel universe beside it. For Houck Chapter, whose residents were just starting to get together enough money to build their own roadside businesses, it was a disaster.

Today, a few of the curio stores remain, but most have scaled back their operations. At the ersatz way station Fort Courage, the gas pumps and restaurant are defunct, and the trading post no longer stocks groceries for the locals.

Ironically, Houck is finally in a position to set aside land and lure in some businesses ... but is it 30 years too late?

"We'd love to tap into that traffic that's zooming by 24 hours a day," said newly elected Chapter President Charles Morrison, "but we need to do a lot of market research before we invest anything."

What would the Navajos have to offer that the bilagáanas don't? Authenticity for one thing. The tourists of the 1950s were happy to buy an arrowhead made in Japan and sample the glitz of the Hollywood West, but if they had parked their cars long enough to talk to the locals, they would have discovered a real West far more fascinating than any John Wayne movie.

Houck is home to Anasazi ruins dating back to 800 A.D. You can hardly walk around here without stepping on a pottery shard.

Later, it was traversed by the Dominguez and Escalante Expedition, a stagecoach route, Lt. Beale's ill-fated Camel Corps, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad ... if you could describe the history of Houck in one word, it might be "bypassed."

It is probably fitting that the chapter is named after a mail carrier, James D. Houck, who established a sheep ranch and trading post about eight miles west of the New Mexico/Arizona state line, according to Austin Sam's exhaustive history of the chapter.

But being on the way to everywhere creates its own history. The Navajos of Houck - or Ma'iito'i (Coyote Springs) in Navajo - had a ringside seat as history passed by in front of them.

They learned about the Depression from the hoboes who jumped off the train to bum a meal off the generous locals, who coined a Navajo word for the hapless men: na'aljidii, or "person carrying something on his back."

They learned about airplanes when they started flying overhead (once again, Houck found itself in a transportation corridor). Watchman, 48, recalls his grandmother describing the first plane she saw while she was out herding sheep with a sibling.

"They had no idea what it was," he said. "They ran and hid under a tree."

But while the Diné were learning about the outside world, that world took little interest in them. Houck was not part of the Navajo Reservation until 1934, so when Anglos started leasing land from the railroad and building ranches in the 1880s, the locals found themselves with no legal title to land their families had occupied since the Long Walk.

Fortunately they found an ally in the local Catholic priest, Fr. Anselm Weber, who studied the land laws and helped the Navajos prepare allotment claims.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Government laid claim to every odd-numbered section along the railroad right-of-way.

To this day, Houck is one of the most frustratingly checkerboarded chapters on the Navajo Nation.

"The NHA prepared a housing plan for us," said Morrison. "It's a nice, pretty picture. There's a 'but' - it's on a mixture of trust, allotted and private land. It would take us forever to get all the clearances we need to build those houses."

Morrison, who used to work for the Navajo Nation Land Department, is looking forward to tapping into the Cobell settlement's fund for buying up fractionated land holdings.

"That could really help us," he said. "They're going state by state, so we have to wait until they get to Arizona."

Waiting is something Houck is very used to, but there's one thing that needs to be addressed immediately: the cemetery.

The chapter's cemetery is completely full, and the Catholic cemetery at the beautiful old mission, St. John the Evangelist/St. Kateri Tekakwitha, has only two more gravesites available.

"People are starting to bury their loved ones on their homesites, which they're not supposed to do," revealed Morrison.

The chapter is in the process of acquiring at least 15 acres for a new cemetery.

Houck is doing better for its living members. More than half the residents have running water, and bathrooms are being built in preparation for the next water line extension. All but the most remote residents have electricity, and since running electric lines to them would be prohibitively expensive, the chapter is recommending they look into Navajo Tribal Utility Authority's individual solar and wind systems.

"We're going to invite NTUA out here to make a presentation," Watchman said.

And as for the future of this fascinating chapter? What else but transportation would play a role?

Watchman notes that motorcycle clubs and old car enthusiasts are rediscovering Route 66, and he'd like to see America's Highway rise again.

It needs to be repaved, he said, so people aren't afraid to drive their meticulously maintained vintage Fords and Chevys on it, and then, it needs some Navajo businesses for motorists to patronize.

Watchman's version of the future Houck is something like a Navajo Seligman, Ariz., with Route 66-themed shops, authentic Diné restaurants and plenty of outlets for the excellent craftspeople who still live here.

In the meantime, if you want to meet some real Indians and learn some real history, Houck awaits those not in too big of a hurry to take the exit and bump along the Mother Road.