Poised for progress

Tohatchi can develop if it chooses to

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 88th in the series. Some information for this series is taken from the publication "Chapter Images" by Larry Rodgers.)

TOHATCHI, N.M., May 29, 2014

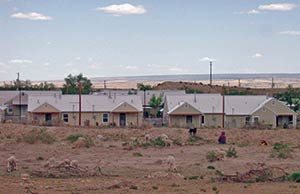

(Times photo - Cindy Yurth)

In front of a new housing development, a shepherd takes a break. Tohatchi's ranching economy has been largely replaced by jobs in nearby Gallup.

It's hard to imagine a chapter on the Navajo Nation with more development potential than Tohatchi.

It straddles busy New Mexico Highway 491, is close enough to Gallup to commute (but far enough to need its own businesses) and is on the route of the Navajo-Gallup water pipeline.

A clinic is here, several schools, nine churches, some Anasazi sites and beautiful Chuska Mountain scenery.

Yet there's almost no private business other than two roadside convenience stores.

"We like our quiet and we like our privacy," said Edwin Begay, a former two-term chapter president who's now running for McKinley County Commission. "We're our own worst enemies."

Begay, whose second term ended in December, said getting the conservative people of Tohatchi to accept businesses was like "pushing a boulder up a hill."

Which shows, the Republican commission candidate said, that the modern residents of Tohatchi don't know their history.

Begay is a descendant of Chief Manuelito, who made his home here with his wife Juanita before moving to Coyote Canyon.

According to Begay, Manuelito and Juanita had a daughter who was so assertive she was known as "Manuelito No. 2."

"She was one of the first entrepreneurs on the reservation," Begay said. "She recruited 20 women to weave rugs for her, which she took down to Tobe Turpen's trading post in Gallup and traded for food, which she brought back up here and distributed to the weavers."

Manuelito himself was also quite enterprising, according to Begay, raising buffalo for the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial.

Today, said Begay, Tohatchites are content to herd their ever-smaller flocks of goats, cattle and sheep. But they should look to the future, he said.

"Their kids aren't going to herd sheep," said the human resources director for Ch'ooshgai Elementary School, which his grandfather helped to found. "They're going to be doctors and lawyers and professionals."

Today, if you work in Tohatchi, you're most likely an educator. The chapter boasts two elementary schools, a middle school and a high school. But it is far from its heyday as an education mecca.

One of the reservation's first BIA boarding schools was built here, drawing students from as far away from Tuba City.

"They probably had 800 students back then," Begay said. "From what my dad told me, the whole area where the town is now was the pig farm for the school."

The school drew development: homes, businesses and a clinic. Tohatchi became the center for the BIA's District 14, encompassing Naschitti, Twin Lakes, Mexican Springs, Tohatchi and Coyote Canyon.

Remnants of that thriving era can be seen in the plethora of beautiful stone buildings -- all now abandoned because of an asbestos water pipeline that served them, Begay said. As chapter president, he asked for the BIA land to be transferred back to the chapter, a transaction that's still in progress.

"It would be nice if we could reclaim the buildings," he mused, "but at least maybe we could tear them down and have NHA put some new housing in."

Even before the BIA era, Tohatchi was a thriving place. Navajos settled this area after becoming herders because of the good grazing on the naturally terraced east face of the Chuskas. As with the other settlements along the range, the inhabitants of Tohatchi gradually progressed up the mountains with their flocks in the summer, then back down to the valley floor in the fall.

They often had to defend their flocks and children from the marauding Spanish, and Begay claims he occasionally spies a rusted Spanish sword when riding his horse on top of the ridge.

"I just leave it alone, because I know that's where someone is buried," he said. "We respect that here."

After the Long Walk, many Navajos heading to Fort Defiance settled here instead, Begay said. "They saw the ch'ooshgai (pine trees) and knew they were home," he explained.

Unlike a lot of the surrounding chapters, Tohatchi is on sound financial footing, thanks largely to Begay and his "penny-pinching" ways.

"When I left office, we had a carry-over of $400,000," he said. "We had paid off two huge backhoes and two huge graders."

Begay had investigated grants from the state of New Mexico and found quite a few lying around chapters that had never gotten around to using them.

He convinced the state to divert the money to Tohatchi, where it was used to fence the cemetery and fund ongoing projects like a fitness trail and a community farm.

When the Times visited the chapter Tuesday, the current chapter officials were meeting with a representative of the Navajo Nation's Land Department to learn how to do a community master plan in preparation for becoming a certified chapter. Begay hopes the present leaders can implement the development he couldn't quite get started.

Harlan Charley of the Land Department, though, was urging the chapter officials to measure twice and cut once.

"You have a prime spot for development," he told them, "but you should have a policy of no more development until you guys plan this out."

With a little planning, Charley urged, Tohatchi could be a wonderful place to live.

Begay agrees.

"I've lived in Manhattan, I've lived in Washington, I've lived in Chicago," he said, "but I'm glad to be home. New York smells like hot dogs and exhaust fumes. Washington is all white marble. You miss the smell of manure. You miss riding your horse up the mountain.

"This is home."

How to get The Times: