In the hidden valley

Mariano Lake has found creative ways to do things on its own

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

MARIANO LAKE, N.M., August 29, 2013

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 49th in the series.)

D riving north from Church Rock, past the red cliffs and the eerie white stone sentinels, you arrive in a high green valley so expansive it commands you to take your foot off the accelerator and draw a deep breath.

You don't even have to ask the locals why people settled here; it's obvious even to someone who has never owned livestock: This is ranching country.

"People came over to raise sheep," said James R. Bennett, 64, a lifelong resident of Mariano Lake.

It's still beautiful, but clearly, this is a chapter that has seen better days. Stucco is chipping off the 1980s-vintage NHA homes; the roads are rough. The uranium mine is shuttered, leaving a radioactive Superfund site. The lone remaining business, a trading post, shut its doors about 10 years ago and has been torn down. And the lake ... well, these days it's more of a marsh.

"When I was a young guy," Bennett said, "the lake used to fill almost clear up to the road. There were a lot of birds - all different kinds of ducks and stuff."

There was the trading post, where people used to meet and greet, and a dock for fishing.

"People came from all over to fish in our lake," Bennett said proudly.

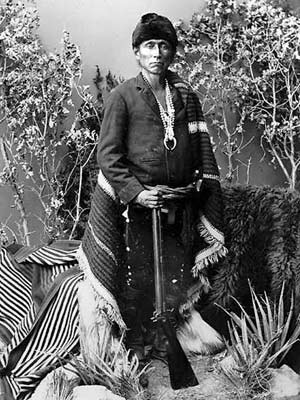

Chief Mariano

The lake has a long history. Coming back from the Long Walk, Chief Mariano Martinez settled here. Mariano, a signator

y to the original 1849 treaty with the U.S. government, was already elderly, but he convinced the other settlers to build a dam to create a large, shallow reservoir for livestock and farming.

Impoverished from their sojourn at Fort Sumner, the Navajos had only primitive stone and metal tools, and used rugs and blankets to haul earth. Still, they managed to create a reservoir that exists to this day ... albeit as a ghost of its former self, thanks to the drought.

The lake is almost gone, and the chapter's other claim to fame - The Gulf Mineral Mine, which produced uranium from 1977 to 1982 - is closed and fenced off, a radioactive Superfund site awaiting remediation.

The 31-acre mine site, presently owned by Chevron, includes a 500-foot-deep shaft, waste piles and surface ponds.

In 2011, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced it had reached an agreement with Chevron to study soil contamination in the area of the mine, including 10 nearby residences and two water wells, as the first step toward cleaning it up. The research phase is ongoing.

So what does Mariano Lake have going for it now?

For one, many of the chapter's 800-odd residents have both running water and electricity, and the school bus routes are gradually being graveled. Both a power line and water line extension are in the works, according to the chapter's president, Anthony Begay. One of the water lines will go past the mine, and Chevron and the EPA are obligated to haul away any radioactive soil that's unearthed.

Finding detours

As it did back when Mariano was in charge, this independent community has found some creative ways to get things done.

So far it's the only chapter to go through the BIA to acquire the right-of-way to its chapter compound access road, meaning it could use state and chapter funds to chip-seal it rather than waiting on the BIA.

Once it had the right of way, the chapter allowed the road construction company that was working on Navajo Route 11 to set up shop in front of the chapter house - in exchange for which the crew gave the chapter its excess asphalt.

"I got some guys together and got out there with my own truck and my own trailer, and started filling potholes at the NHA housing," Begay said. "The great thing was, the people in the houses came out with their shovels and joined us."

The chapter "utilizes the heck out of" the BIA's Eastern Agency office in Crownpoint, Begay said.

"We don't have to bother Ms. (Navajo Regional Director Sharon) Pinto about anything," he stated proudly. "Crownpoint is happy to help us."

If the tribe is not forthcoming with funding for projects, Begay and his crew at the chapter hit up McKinley County, the BIA or the state of New Mexico.

"The way I see it," said the 40-year-old second-termer, "this job is about getting around the politics and getting things done."

Among the community's other assets, Mariano Lake Community School, a BIE boarding school, serves 195 students from all over the area and is the community's only employer, other than the chapter.

Navajo Route 11-49 was paved in the 1990s, making Gallup a quick commute of about half an hour and enabling residents to take jobs there. (On the downside, the community's trading post couldn't compete with Gallup's supermarkets, and folded about 10 years ago.)

"I don't know if we'll ever be a place with a lot of business," admitted Begay. "We're not exactly on a major thoroughfare."

Still, the chapter is eyeing some allotments along the Rocky Canyon Road, which is scheduled for improvements and will be the major commuting route to Crownpoint.

Playing the checkerboard

While most Eastern Agency chapters complain about checkerboarding, Begay sees the advantages.

"It's much easier to deal with allotted land than with tribal trust land," he said.

Following in Mariano's footsteps, the chapter took advantage of last year's dry summer to build several earthen dams that are paying off with the current monsoon.

"Navajos are always saying, 'Water is life; water is precious,'" said Begay, "and then we just watch it run downhill."

The chapter jumped on the feral horse problem years ago, Begay said, and ranchers are now educated that "they have responsibility for their livestock; we're not going to hold their hand."

In exchange, however, the earthen dams make it easier on them to water their herds. Responsible ranchers are reaping the benefits of restraint; this is a chapter where you will see healthy native grasses where others have tumbleweeds and sand dunes.

On the long-term drawing board are a senior citizens' center, a veterans' center and a transfer station.

Meanwhile, how do the people of Mariano Lake spend their time? Bennett's daughter, Jerrilyn Bennett, 31, disputes the notion that there's nothing to do here. "There's stuff going on at the school and the chapter house," she said, "and if you're Christian, there's always a revival to go to."

In the fall, the piñon picking is legendary.

She and her father both like the fact that, just a half-hour from the relative hubbub of Gallup, this giant valley is a different world.

"It's quiet," said Jerrilyn.

"I just like to be here and meet all my relatives," opined the elder Bennett, who recently retired from the school, where he was a cook. "Every time they have a chapter meeting, people come by, we shake hands ... it's just a nice place to be."

Contact Cindy Yurth at cyurth@navajotimes.com

Mariano Lake at a Glance

Name - Upon returning from the Long Walk, Chief Mariano Martinez supervised the building of a long dam to capture water for crops and livestock. Impoverished by the years at Fort Sumner, the people had only crude hand tools and rugs to haul the soil. Still, they managed to build a sizeable dam that exists to this day. The chapter continues to bear Mariano's name, and some of his descendants still live there. After years of drought, however, the lake is a shadow of its former self.

Population - 823 at the last Census

Land area - 67,000 acres

Famous sons - Chief Mariano Martinez, long-time Council delegate Young Jeff Tom, singer Dan Jim Nez, and the current chapter vice president, J.R. DeGroat, who designed the Navajo Nation flag

Assets - good grazing land, water, a BIE boarding school

Problems - lack of through traffic, an abandoned uranium mine that is now a Superfund site

Clans - Hashtl'ishnii (Mud People), Tsi'najinii (Black Streaked Wood), Tó Bazhní'ázhií (Two Came to Water), Kin Yaa'áanii (Towering House), Biih Bitoodnii (Deer Spring)

Claim to fame - Straddling the Continental Divide, Mariano Lake has the highest average elevation of any chapter on the reservation