Bypassed by progress

Tsé Si Ani's glory days are in the past -- or the future

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi" Bureau

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 102nd in the series. Some information for this series is taken from the publication "Chapter Images" by Larry Rodgers.)

LUPTON, Ariz., Sept. 4, 2014

(Times photos – Paul Natonabah)

TOP: Voters walk past Tse Si Ani Chapter House after voting in the Navajo Nation Primary Election last Tuesday.

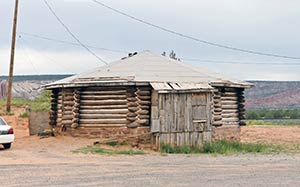

BOTTOM: An old traditional style hogan was used as a “smoke house” with drive-up window that catered to mostly semi-truck drivers. It was owned by former Council delegate Tom Shirley.

Cowboys and Indians, outlaws and in-laws, steam trains, calvary and Chinese laborers -- every cliché of the Old West could, at one time or another, be found right here in Tsé Si Ani Chapter.

"When it comes to colorful histories," said Navajo Code Talker and Tsé Si Ani native Roy Hawthorne, "I don" t think you can find a chapter more colorful than this one."

Tsé Si Ani is literally colorful too -- lined by red-and-white striped cliffs that weather into pillars that themselves conjure colorful characters. One so resembles a Coca-Cola bottle that Greyhound buses trundling down old Route 66 used to stop so their passengers could take a picture of it.

For years, over a century really, Tsé Si Ani was the place to be. It was a major crossroads Ñ less than 30 miles south of Fort Defiance, about the same distance north of Zuni and heading east or west, you could go clear across the country on a network of roads that has now been consolidated into Interstate 40.

"What I" ve always said about Lupton (the former name of Tsé Si Ani) is that you can start here and go anywhere," Hawthorne said.

For him and the six other code talkers who were born here, that meant clear across the world to the South Pacific, where they used the Navajo code to help win World War II.

Hawthorne isn't sure why there were so many code talkers chosen from Lupton.

"I'm sure patriotism entered into it," he mused. "But for me and I think most of the others, it was Number One, adventure and Number Two, we didn" t want to starve to death."

Actually starving to death was a lot less likely in Lupton than it was on the rest of the rez. The year Hawthorne was born, 1926, the U.S. government began an almost arrogantly ambitious project: a road that would connect the meat-packing and manufacturing mecca of Chicago with the port of Los Angeles. It was later numbered Route 66.

By the time Hawthorne came home from the war, Lupton was starting to become a tourist paradise. Lured by the promise of meeting "real Indians," motorists pulled off the newly paved highway to buy rugs, crafts and trinkets and have their pictures taken with the Navajo proprietors of the roadside stands.

"Some people did quite well," Hawthorne said.

Indian Miller

There were the legitimate shops with authentic crafts, and also the more lurid roadside attractions. Some bilagáanas muscled in on the action, of course, most notably the infamous "Indian Miller," who, according to Hawthorne, was neither Indian nor, in all probability, really named Miller.

"He and his wife lived in a big cave in the cliff," Hawthorne said. "People said he was from Canyon Diablo, which was as far as the railroad had gotten at that time, and that he had killed a man there and was here fleeing the law."

The local Navajos refused to call Miller "Indian" and simply referred to him as "Braided Hair."

"He had all kinds of animals up there, even mountain lions," Hawthorne recalled. "Anything to attract the tourists. He put up a sign that said, "Entering the desert. Better buy your water bag now."

" Water bags, explained Hawthorne, were leak-proof canvas bags filled with water.

"The water would soak the canvas and evaporate, cooling the water inside," he said. "They were quite popular."

The advent of I-40

Those were Tsé Si Ani's salad days. But they were about to wilt.

In 1960, the feds started replacing Route 66 with the even more ambitious Interstate 40, bypassing Lupton except for a single exit at Navajo Route 12.

Three years later, I-40 was opened to traffic. In a few short years, one of the more prosperous chapters on the Navajo Nation was reduced to little more than a ghost town, as shop after shop shuttered its doors.

Savvy Diné businessmen were reduced to laboring on the Santa Fe Railroad or hitchhiking north to Idaho to pick sugar beets.

"The thing about those jobs," Hawthorne said, "is that they were somewhere else."

Families began to disintegrate; alcohol took its toll.

"If you look at Tsé Si Ani today," Hawthorne said, "you will see a very depressed area."

The handful of tourists who do pull off the Interstate, however, will find an area rich in stories, like the (absolutely true) tale of when the Army brought camels through here. You can still occasionally find remnants of the camps in the cliffside where Chinese railroad workers squatted and cooked their dinner in woks over open fires, and even more ancient artifacts from the Anasazi who made their homes on the mesa tops and farmed the valleys a thousand years ago.

Old-timers can point you toward the Place where the Lightning Lives, a high point where two mesas come together that has been struck so often it is glossy black (but please don" t go up there, there" s a strong taboo against disturbing the spot).

Maybe you" ll even find the train robbers" cached treasure that old Braided Hair was always looking for.

For sure you will find scraps of the glory that was Route 66.

Is there any chance Tsé Si Ani can rise again? At 88, Hawthorne doesn" t think he" ll live to see it.

"Until the tribe can change their laws about starting businesses," he said, "everyone" s just going to go to Gallup."

How to get The Times: