Sandwiched

Between Gallup and Zuni, a Navajo chapter slices out an identity

BAAHAALI, N.M., October 4, 2012

(Times photo — Cindy Yurth)

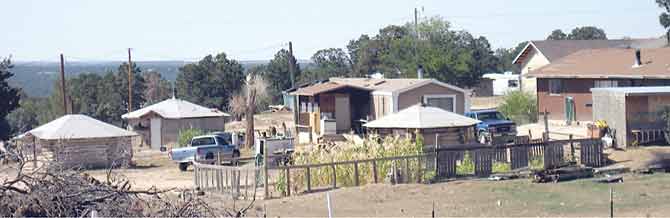

TOP: This neighborhood high on a hilltop in Baahaali Chapter has mostly sprung up since the road was paved in the 1980s, according to locals.

SECOND FROM TOP: Judy Davis, 63, learned lots of local history from her great-grandmother, a leader and medicine woman. "But I wish I had paid more attention," she says

J udy Davis is a reluctant Christian.

In her heart, she still believes the traditional ways are best. But, like the Biblical Belshazzar, she saw the writing on the wall.

"The old medicine men, the real ones, were dying off," she sighs, and the children of Baahaali seemed to be adrift. She decided Christianity would at least provide some firm moral footing.

So, in case you're wondering why the little white Baahaali Church of God is sitting there on Davis' grandmother's land, and why a family that once included a powerful medicine woman is Christian today, that's the story.

In some ways, it's the story of Baahaali Chapter. Twenty miles south of Gallup, 30 miles north of Zuni and just over the ridge from Fort Wingate Military Reservation, the fiercely proud Navajos of this beautiful, heavily forested chapter have had to trade the convenience of living near jobs and amenities for a certain amount of cultural loss.

It wasn't readily apparent until the present generation, according to Davis, 63.

"The youth, their role models are television and people in big cities," she said. "They don't dress like Navajos. They don't talk like Navajos. They don't act like Navajos. I wouldn't even call them Navajos."

Willard Martinez, the chapter's 22-year-old custodian, would have to agree to some extent.

"The youth?" he asked. "You don't really see them around here."

That's certainly apparent on Oct. 1. The tribal paychecks and public assistance checks have come out, and Baahaali is something of a ghost town. Even the chapter staff is in Gallup; those people you see in the office are the staff of Chichiltah Chapter, who is borrowing office space at Baahaali while their chapter is being renovated.

Actually, for being almost surrounded by non-reservation land, the chapter was pretty isolated and self-sustaining until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the two main roads were paved.

Suddenly, Gallup was an easy daily commute, and many chapter residents got jobs there.

On the minus side, people abandoned their flocks and cornfields, and became entirely dependent on the outside world for their sustenance, according to Davis. To this day, there are no businesses in Baahaali, although there are four churches.

A lot of people moved to be closer to the paved road; while the settlement used to be concentrated along the washes that irrigated the fields, the newer homes follow the roads.

The roads may be paved, but they're still precarious. One of the most dangerous things you can do in Baahaali is drive.

Blue Medicine Road, the main road in from state highway 602, is crumbling on either side, causing motorists to hug the middle. Most Baahaali residents know someone who has been involved in a head-on collision, or narrowly avoided one. The three one-lane bridges don't help matters.

There may be some relief on the horizon; McKinley County Road Supervisor Jeff Irving says the area is high on the list for improvements.

"We're looking at that area as a test area for some new materials," Irving said, adding that road construction season is almost over for the year, but residents should look for his crews come spring.

With only 1,000 people scattered across 45,000 acres, Baahaali's low population density makes it a low priority for services like road construction. But things are looking up.

Elouise Washburn, 53, remembers when her grandmother's hogan was about the only structure atop the hill that holds the water tower; now it's a flourishing neighborhood with a 360-degree view.

Washburn concedes the chapter has lost some of its Navajo flavor since she was young, but she thinks it's coming back.

She and another volunteer teach rug weaving at the chapter house in the summer, and the traditional skill has become quite popular with the younger crowd.

"Some of them came back for the fourth time," she says. "They surprised themselves learning that they could do that."

Davis' daughters are fixing up two of the old family houses behind the church as retreats from their hectic jobs in the city, and on this day she's watching her two cute grandkids, 3 and 2, frolic in the sun while her daughter is at work.

The day school was recently rebuilt, and the local Head Start is full of the newest generation of Baahaali residents. They hold the key to the chapter's future.

Baahaali got its Navajo name back in 2008 (it was formerly known by the English translation, "Bread Springs

"). Can it get back its culture too?

That remains to be seen, but in the meantime, everyone seems to agree Baahaali is a great place to live.

"Over there is my father's house, those are my aunties back there," Washburn sayids, pointing out the surrounding buildings. "I'm surrounded by family, I have my garden, and I have a great view. I love living here."

Baahaali at a glance

Name — "Baahaali" translates to "Bread Springs" or "Bread Flowing Out." There are three stories on the origin of the odd name. The actual spring is high on the ridge that separates the chapter from Fort Wingate. Some say rounded, loaf-shaped rocks gave the spring its name. Others say it has to do with the soldiers stationed at Fort Wingate throwing their leftover lunch into the spring. Another version is that the Zuni, collaborating with Spanish or Americans, laid an ambush for the Navajos by leaving loaves of their delicious oven bread by the spring, hoping to lure hungry warriors.

Population — about 1,000

Area — 49,273 acres

Police officers — 1

Businesses — none