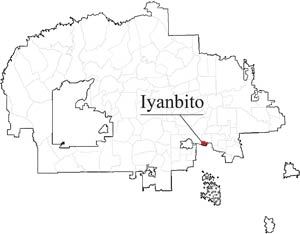

Where the buffalo roamed

After tough times, little Iyanbito is poised to grow

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

IYANBITO, N.M., May 23, 2013

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 36th in the series.)

T he details of the story are a little hazy.

Some say the buffalo got loose during a train derailment; others say they stomped down a pen at Gallup's Intertribal Ceremonial. A 1998 article in the Santa Fe New Mexican says they were brought in by the state's Fish and Game Department as game animals in the 1960s.

But one thing is for sure: There once were buffalo here at Buffalo Springs (the literal translation of Iyanbito).

"I remember seeing them on my way to school in Gallup," said Chapter President Steven Arviso. "They were there for years."

The story Arviso heard is that the Ceremonial used to ship in buffalo for a buffalo riding competition. One day, for reasons known only to them, the massive mammals stomped down their pen and stampeded.

"They ran all the way to here," Arviso said, "and then they stopped."

The bison congregated around a small pond that has since dried up. They were there for years, Arviso said, until the state rounded them up and herded them across the highway to a pasture at Fort Wingate.

There they stayed until, in 1995, Fish and Game decided they were too thick and organized a hunt to thin them out.

This triggered a massive protest by local Natives and animal rights groups that finally made its way to court. A judge shut down the hunt, but three years later some of the animals were getting so old that their teeth were ground down to nubs and they died of starvation, triggering a protest from the pro-hunt faction. Tired of the controversy, Fish and Game ended up auctioning the animals off (this triggered a protest from the Pueblo tribes, who wanted the buffalo but because of the animal's sacred status in their tradition, could not pay money for them.)

Now all that's left of the vexatious herd is the name of one of the Navajo Nation's tiniest chapters.

It could be argued Iyanbito is slightly less interesting (though safer) without its shaggy citizens, but small as it is, it's still a place that can't seem to stay out of the news.

"You would think," said Arviso, "that a chapter of 29,000 acres and 900 people would be an easy place to manage, but that doesn't seem to be the case."

In 2010, Iyanbito hit the headlines when the Navajo Nation's Ethics and Rules Office uncovered a conspiracy between chapter officials of Iyanbito and Manuelito chapters to defraud the chapters out of $100,000.

Iyanbito's chapter president and several other staff and elected officials were out on their ears, leaving the bewildered newly elected vice president - Arviso - a virtually staffless chapter with coffers so empty they echoed.

"They had stripped us clean," Arviso recalled. "I was like, 'What am I to do?'"

The first thing he did, he recalled, was turn off the lights.

"He ended up reaching into his own pockets to pay the bills," confided Marvin Murphy, the newly elected president of the chapter's Land Use Planning Committee.

Needless to say, it took a while before anybody would give Iyanbito money again. But Arviso has worked diligently to make the chapter a respectable place, and recently New Mexico's Tribal Infrastructure Fund gave the Iyanbito its first big grant since the scandal: $200,000 to plan and design a new chapter house.

"We're very excited about that," Murphy said.

Another thing that's keeping Iyanbito in the news is the ill-starred solar project proposed by Nabeeho' Power.

Three years ago, about the time the embezzlement scandal was breaking, the company received a permit from the tribe's Economic Development Division to start building at Iyanbito's 320-acre industrial park.

The project is wildly unpopular with the locals, who so far have passed nine chapter resolutions against it, but it's scheduled to go before the Council's summer session, according to the chapter's Council delegate, Edmund Yazzie (Churchrock/Iyanbito/Pinedale/Smith Lake/Mariano Lake/Thoreau). Because the project has to do with energy, it must be approved by the Council as a whole.

Yazzie believes the people have spoken - many times - and he's not about to sponsor the legislation, but another delegate from outside the area has taken up the banner.

"I need to talk to him," said Yazzie, who happened to be in Iyanbito Tuesday for a meeting with the chapter's senior citizens. "I would tell him, 'Put yourself in my shoes. If this development was going on in one of your chapters without the approval of the people, and I sponsored it, how would you feel?' I don't like the term 'stabbed in the back,' because it's too strong, but I can't think of another metaphor for what's happening here."

Arviso said the locals feel overlooked.

"Had they (Nabeeho' Power) worked with the chapter from the start, it might have been a different story," he said. "They just came in and started building."

According to Arviso, arguments against the project include that it would be an eyesore and interfere with grazing, and wouldn't supply any benefits to the chapter.

Nabeeho' Power did not reply to an email by press time.

So what kind of development would be good for little Iyanbito, whose business prospects at the moment consist of a defunct gravel pit?

Murphy has some big plans.

This pretty chapter with its soaring orange cliffs would be the perfect site for the Navajo Nation's first golf course, he believes - designed by none other than Diné golfer Notah Begay III.

This could be supplemented by hiking, biking and ATV trails for more adventurous tourists, and services to support them.

Arviso is determined to get Iyanbito certified during his administration, but with a temporary community service coordinator and the accounts maintenance specialist position vacant, it's an uphill battle.

Just last year, the chapter was the recipient of a nice-looking Navajo Housing Authority development, but since it's within commuting distance of Gallup, the homes were in high demand and, according to Arviso, most of them were snapped up by people from outside the chapter.

"If we get certified," he said, "we can apply to HUD for our own housing grant and set our own rules," including preferential treatment for chapter residents.

About 80 percent of the homes in this suburban chapter have running water and electricity, and close to 100 percent could be plumbed when the Gallup-Navajo pipeline is completed, Murphy said.

Feral horses aren't a problem with Murphy's dad, the hawk-eyed Wilbur Murphy, presiding over the land board, but there is one big obstacle to development: the chapter is trapped by the train.

According to Arviso, the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railroad is booming. Trains sometimes stretch from Fort Wingate to Church Rock, N.M. And sometimes they stop for a half-hour or more.

There's no way to leave Iyanbito that doesn't cross the railroad tracks.

"We need an escape route," said Arviso.

The logical place for one would be behind the red cliffs, but that area is already plagued by partying and illegal dumping, and both Arviso and Murphy are afraid building a road would make it worse.

"We're looking at the possibility of building a road and closing it off except for emergencies," Arviso said.

There's Iyanbito's share of Fort Wingate across the way, ripe for development with its I-40 access, but that's still owned by the federal government, which has said it won't hand it over until the Navajos and Zunis come up with a plan to share it.

Yazzie told the seniors he's working to add the "sheep lab," 1,740 acres of federally owned land adjacent to Fort Wingate, to Iyanbito Chapter as part of a 360,000-acre land swap currently being contemplated by Congress ... but that's down the road as well.

So there Iyanbito sits, just 20 miles from Gallup, bisected by a major railroad and a major freeway ... an ideal place for development that, for all kinds of reasons, has not yet happened.

Maybe it should bring back the buffalo.

Iyanbito at a Glance Name - a corruption of Ayanibito, Buffalo Springs, after a pond where buffalo reportedly congregated. Before that, the area was known as Tl'izi Ligai (White Goat), after a trader who would only take white goats.

Population - 890 at the 2010 Census; probably closer to 1,500 with the addition, last year, of 70 Navajo Housing Authority units

Land area - one of the Navajo Nation's smallest chapters at 29,000 acres

History - Many Navajo settled in the area after taking jobs at the U.S. Army Depot Fort Wingate.

Major clans - Since people came from all over to work at Fort Wingate, nearly every Navajo clan is represented here.

Problems - The only access to the chapter crosses the railroad tracks, leaving residents stranded when the train stops.

Current issue - a solar project the community does not want but may be powerless to stop