Few farms, but good ones

Many Farms' agricultural legacy threatened by drought

By Cindy Yurth

Tséyi' Bureau

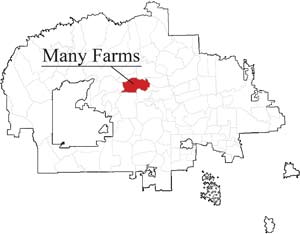

MANY FARMS, Ariz., August 22, 2013

(Editor's note: In an effort to chronicle the beauty and diversity of the Navajo Nation, as well as its issues, the Navajo Times has committed to visiting all 110 chapters in alphabetical order. This is the 48th in the series.)

T he dream is back," quips Many Farms Community Services Coordinator Danny Francis, playing off the title of a July 11 Navajo Times article.

The article, about the disappearance of Many Farms Lake, was titled, "The dream just ended."

The reservoir is, in fact, back, thanks to the recent monsoon that filled the washes that feed it. But, like a dream, it's illusory.

"It's only about a foot deep," admits Francis.

A decent monsoon has given the Navajo Nation a slight reprieve, but it will take a lot more to bring precipitation up to normal.

That's bad news for Many Farms Chapter, whose name reveals just how deep its agricultural roots go.

These days, you have to drive around Many Farms for quite a while before you find even a single farm.

Here's a nice cornfield, just off the lakeshore, by an interesting two-story house.

Eddie Sage answers the door, a fit-looking hexagenerian. Sage is just re-entering the agricultural life, having spent much of his adulthood as a grocery-store butcher in Albuquerque.

Last year, he had a heart attack and his doctor told him to slow down. Not wanting to become another middle-aged Native American statistic, Sage quit his job and moved back to his home chapter, where he is farming his sister's land while she commutes to work at the Chinle Valley School.

"It's nice and quiet out here," he says. "The city was killing me."

Sage cut out the bologna sandwiches and eats mostly rice and home-grown vegetables now. In addition to the farm work, he walks or bicycles to the lake almost every day. As if to show off his newfound health, he sprints to the house and comes back with a sack of kneel-down bread. He makes his living selling the bread and roasted corn at the Chinle flea market.

So here's a positive story of a family farm still doing well. Or so it would seem. But ask Sage how Many Farms has changed since his childhood, and his answer is instantaneous.

"It doesn't rain any more," he says.

This chapter sprang up around the reservoir, which was dammed in 1937. It soon had a general store and a one-room schoolhouse. In 1941, it became the site of the Navajo Tribal Slaughterhouse and Cannery, supplying meat to many of the schools and hospitals on the Navajo Nation and even shipping some to the Armed Forces.

These days, says Francis, the major employers are the schools — Many Farms has a BIE grant elementary school and high school as well as a public elementary — the Indian Health Service and the tribal government. In other words, the same as most chapters.

Bisected by U.S. Highway 191, Many Farms does have good potential for roadside businesses. Two convenience stores manage to thrive practically next door to each other.

The infrastructure is better than in most Navajo chapters; the vast majority of established homes have both running water and electricity. After many years of waiting, Navajo Route 8084 — the 22-mile shortcut to Tsaile — is about to be paved, to the jubilation of the college crowd.

But with agriculture mostly kaput, this is a chapter in search of a new identity.

Tourism is a possibility. The lake could easily draw campers, and, if it fills up again, fishermen; it was home to some monster cats in the past.

Or maybe, suggests Francis, the slaughterhouse could be reborn ... this time to process the feral horses that are Many Farms' largest, if unintentional, crop.

If Sage has moved back to the chapter for his health, perhaps he is not the only one. Developing hiking and biking trails along the lake might draw in some active retirees.

Or, maybe, the farms will come back.

That's what Roland Tso is hoping for.

"There's water here, even with the drought," says the chapter's grazing official, who has never been a man to mince words. "We just need to catch it before it flows into the San Juan."

According to Tso, the local farm board is looking at several new irrigation projects that will make a lot of land arable again. But he thinks the older generation needs to get out of the way.

"People have huge tracts of land, like 2,000 acres," he says. "They're only farming small parts of it. We need to divide those up and pass them to the next generation. They're more likely to diversify and grow something besides corn. Then we just need to get a farmer's market going, and market it locally, like we used to do with the slaughterhouse during the war."

It's a nice dream for down the road.

For the moment, however, Many Farms is working on some basics, like getting certified. A non-profit development entity, Dá'ak'e Halani Development Inc., is already in place to decide how to spend the money once it starts rolling in. Francis' dream is a multi-purpose center where the community can come together for events. Tso thinks the chapter should dream much bigger.

"If you go back in the past, we had the slaughterhouse, we had a Laundromat, a restaurant, even a car wash," he says. "We let it all slip away. We need to bring it back, and more."

Many Farms at a Glance

Name — Shortly after the reservoir was filled in 1937, people started locating along the lake shore to farm. The area became known as "Dá'ák'e Halani" ("Many Fields") which was translated into English as "Many Farms." Before that, the area was known as "To Naneesdizi," "Water Stringing Out."

Population — About 3,000, an increase of 500 people over the last 10 years

Land area — 168,000 acres

Major clans — Because people moved here from all over to build the dam and farm, most Navajo clans are represented here

Assets — Two elementaries and a high school, two convenience stores, a dental clinic, U.S. post office, a major north-south thoroughfare and of course the 25,000-acre-foot lake.

Problems — The lake attracts herds of feral horses. Spurred by concern from the chapter officials, the Arizona Department of Transportation recently replaced the right-of-way fence and cattle guards along U.S. Highway 191, cutting down car-livestock collisions considerably. A roundup was in progress in neighboring Round Rock this week, netting 80 mostly unbranded equines the first day. The drought has also affected this agricultural chapter, changing its once-prosperous farm economy into one of government and service-sector jobs.

Famous son — John Claw Jr., who designed the Navajo Nation seal, was from here. The seal was adopted in 1952.